Overwork by Brigid Schulte

I found this book in the ‘highlights’ section of my local library, and it came at the right time. Since suffering from academic burnout (and depression and anxiety) during my PhD (while having six other part-time jobs to make a living, because my studentships weren’t really enough), I became interested in work and all the social and legal implications around it. I consider myself an artist first (a writer, primarily). Still, I’ve also had a series of jobs to make a living because the money I make from my writing is pitiful and doesn’t even remotely get close to minimum wage. I know this is the case for many of my writer friends (actually, all of them). I’m pretty fine with it. I mean, I know writing as a profession is extremely devalued, and I’d like to fight to change things in that regard. But I also enjoy having other occupations – I’m a social creature by nature and an extrovert. When I was working in retail, for example, I really thrived by serving other people and aiming to make their days better through our short interactions. It not only made me feel useful, but it also made me feel closer to my community. (For context, I worked as a bookseller for a few years.) Now, I despise some jobs I’ve done (ahem, marketing is pretty up on the list, it was too soul crushing) and loved others (being an academic, teaching and researching Creative Writing). But the constant of my job life has been marked by overwork, uncertainty, precariousness, and generally feeling dehumanised by the businesses I have been part of as an employee. Sometimes I’ve wondered if that’s my fault (am I too sensitive, like my grandmother used to say? Am I just weak? Am I just too much of an idealist?) But also, slowly but surely, I come to realise that a lot of systems we are part of are not designed to make us feel cherished, or to make us feel like our development matters or that we are important. On the contrary, we are treated as liabilities, as highly disposable parts.

This was something very clearly stated in Overwork, written by a journalist who has been collecting data on the working practices and cultures of mainly the US, but also other countries. One of the things that surprised me the most about this book is that she explains that in business school, managers are trained to see employers as liabilities, hence why so many companies happily embrace the ever-permanent cycle of redundancies and re-hirings. The data doesn’t support that laying off your employees to then rehire shortly after actually makes more money in the long term (in fact, it costs these businesses money). But in the short term, it sure makes those numbers look better to investors and other higher-ups.

This has been my experience in the twelve years I have been hired to work for companies. It’s interesting because I grew up with the idea (the myth, the fantasy) that a university degree was the natural step to ensure a permanent job in something I enjoyed. I had the role model for that, my mother, a teacher working in a public secondary school. This was a government job, which meant even though she didn’t make much, her job was never on the line. It was an income she could always count on, pretty much no matter what.

I, on the other hand, soon discovered that, sure, a BA and MA (and a PhD) landed me several jobs. All of these were, however, extremely precarious, often minimum wage and demanded total flexibility to work weekends and do extra hours at short notice. At the same time, employers reminded you how lucky you were to have a job at all, which got reinforced by the redundancy cycles.

I felt empowered by reading Overwork because Schulte comes with data and numbers that are quotable and show that businesses that invest in their employees, that make them feel valued, do better. This is because then the staff feels motivated to go the extra mile and give their all to the business. I have had experience of this, times when I had excellent managers who cared about us and inspired us by example and pushed us to be better employees.

‘Understand that burnout and work stress are driven by organizational problems, not individual failings. Yes, deep breathing, long baths and mindfulness can help you manage the stress, but burnout us driven by leaders and cultures. So drop the guilt and begin setting and communicating your priorities and boundaries, which can also help spark change from the middle out.’ (p. 292)

This book also reminded me how tough and inhumane the working laws are in the US. There’s no sick leave by law, and there’s no maternity leave either – all of these are things the company you work for can choose to offer you, but they are not in any way obliged by law. I guess coming from Spain and also living in the UK didn’t prepare me for this. Schulte also reminds us that the system is broken, showing how frequent it is to find people who work a full-time job and then a part-time job or side hustle on top of that, just because the full-time job is not enough to live on anymore. Which again, it’s mind-blowing, but also, the precariousness of many of my jobs in the past is what has pushed me into similar situations (because, at the end of the day, many of us still have to pay rent, or the mortgage, no matter what, or we will find ourselves homeless).

Other chapters of the book describe the interesting phenomenon of working schedules – how they are too long and how they often don’t prioritise the long-term health of their staff, meaning that in many jobs, a work-life balance is just not possible. I remember discussing this with friends – how in the past sure, my grandfather had a very demanding full-time job (and sometimes a second job on top of that to make ends meet) but he also had a wife at home (my grandmother) who was taking of the cooking, the cleaning and rearing the children, all for ‘free’. (Also, my grandparents could feed a wife and four children on one full-time salary, which is not feasible anymore for many of us.) Oh, how things have changed. Sometimes I do wish for a wife, sure, but also – it’s not like I could even realistically afford to have one!

There’s also the chapter on company cultures – how important it is to show that you are ‘working’ and that you are ‘busy’ even if you are really not for many hours, despite having research that shows that shorter work days would encourage more focused work time and make the workforce healthier and happier.

There’s also an interesting study on the four-day week, which has been trialled already in countries like Iceland. What is happening there seems to suggest that this is not only feasible for business but that it may have a very positive impact on society overall, since it will allow more family and community time for the staff.

There’s also an extremely shocking and sad chapter about overwork culture in Japan, and how it can drive people to die by suicide. That was such an interesting case – companies that will promise to employ you for life and never let you off (which in the current climate sounds very tempting to me ), but at the same time will demand you give them pretty much every second of your life.

Another interesting thing about work and gender stereotypes is also included in Japan – how the country offers a year-long paternity leave for men (with their same salary and the possibility to return to their same job afterwards) to incentivise a rise in childbirth in the country. Yet, barely any man goes for it because they fear discrimination from their colleagues and bosses who don’t think that ‘leaving’ your job to take care of a baby is manly. There was an example of a very sweet dad who had founded a ‘dad’s club’ in which he was trying to defend the idea that a good father (a father who spent time with their children and was actively involved in their care and education) was also a good, very manly man.

At the end of the book, Schulte offers a series of notes both for workers and employers, which propose approaches and ideas for both to improve staff experience in the workplace and the sustainability and profit of the business. (So, a rather optimistic ending for quite a grim book.)

‘Foster cultures of trust and transparency. Research shows that this leads to innovation and productivity. Remember, too, that research also shows that when people have choice, challenge, a sense of purpose, and connection to a larger mission, when they are well supported, trusted, and feel respected, then workers are happy, businesses are profitable, and society flourishes.’ (p. 295)

Non-Binary by Genesis P. Orridge

I didn’t know who Geneis P. Orridge was – I had only, if very briefly, heard of them here and there, specially about their rather fascinating art project their embarked on with their significant other, Lady Jaye, to create what they called ‘the pandrogyne’ (they both went through surgery and body modification to look like they were part of a single entity).

This is an autobiography that is the result of a collaboration between Genesis and writer Tim Mohr. It starts with Genesis being born as a baby in Manchester and finishes in the years after Genesis lost their partner Lady Jaye to cancer. In a note at the end, it explains that Genesis themselves died of cancer as well while the book was being produced, so the ending may feel a bit abrupt because Genesis never got to work in it.

I found this a very interesting book about art and the motivation someone can have to follow a very alternative lifestyle guided by the artistic ideals and curiosity rather than more realistic pursuits, as many of us (having to get a job and so on). Even though Genesis does admit throughout the book that all of this was possible because they could count on unemployment money as a creative to cover the basics, as well as several art grants (including those from the Arts Council) that supported their artistic endeavours. Which, in a way, supports my theory of universal income as a saving grace for many of us artists. If we had just the basics covered, I believe many of us would thrive in our chosen artistic careers, doing work that is still very important to society as a whole. Genesis themselves have done valuable work for the arts and the music scene as described in this book.

The part where they narrate their childhood was one of my favourites. It shows the impact education can have on someone young. In one school, Genesis finds freedom to make friends and learn at their own pace, with their creativity being nourished. In the next school (Solihull School, a fancy, private institution they manage to access thanks to a scholarship), they are violently bullied by students and teachers alike. Their description of how this particular institution works is harrowing, yet they recognise that this is the place where they discovered art and occultism and their first collaborators, two other students who would create the collective known as ‘Worm’ with Genesis.

The rest of the book describes their artistic career and their obsession with going against all societal norms and creating something purely original. In fact, the first half of the book (Genesis’ formative years) describes an important moment in their life when they get to meet their literary idol, William Burroughs. This passion for art and originality leads them to quit university and squat in different houses, living in poverty to create different kinds of art. But it’s never a lonely pursuit as Genesis collaborates with many other artists along the way, including Cosey Fanni Tutti (who was in a relationship with Genesis for many years and who has talked about how difficult a person they could be, and how they were often abusive).

It also describes their rise as an artist and musician and how they came to be considered as the ‘godfather’ of industrial music – which Genesis seems quite bitter about after seeing it turn just into another label. This includes the art collective they founded with Cosey ‘COUM transmissions’, their band Throbbing Gristle (which pioneered industrial music) and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth.

The end of the book narrates their experiences as a father of two little girls and also the story of meeting what they consider their life partner, Lady Jaye, and collaborating in different artistic pursuits with her.

I enjoyed this book much more than I thought – Genesis is a very complicated human being (and their many flaws are obvious even in their autobiography), yet their drive and commitment to their art and their vision were refreshing. At the same time, I could see how all of this was facilitated by other people and systems that allowed them to always be healthy enough to create and also enjoy a profitable art career in their later years.

Nightbitch by Rachel Yoder

I assumed I’d love this book… and then I didn’t. Let me unpack things. First of all, the writing was splendid. The concept is great too: the story of a mother with a young toddler who feels overwhelmed (her husband works outside so she can be a house mum) and slowly but surely starts to turn into… a dog?

This was sold to me as a feminist book all about the harshness of the (unpaid) care work of mothers. The main character is quick to recognise her privilege: she had a good job in the arts sector (after being trained as an artist herself) and chose to have a child with her husband. Once her maternity leave ended, she found that she didn’t enjoy being separated from her baby for eight hours or from her mother every day. Her husband kindly offered for her to stay home so she could focus on caring for the baby whilst he focused on working outside. (While, at the same time, saving them some money, I assume, since childcare can often cost as much as one whole salary.) On paper this looks as a great deal for our main character, but, of course taking care of a toddler is a 24/7 job and she’s sleep deprived, and exhausted and she doesn’t have time for anything anymore (least of all, her art and any other activity that could reinforce her sense of identity beyond being a mother).

I don’t have children myself, so really, what do I know? But whilst this main character felt so betrayed by her husband (who sure, worked very hard, but also got to have free evenings and nights where he could actually sleep and rest) I just kept thinking that the solution was… to talk to her husband and ask him to get more involved on his child’s life so the parents can have both eight hour jobs but they can also have times to rest and they can take turns sleeping. Or maybe they could both work but reduce their hours? (I’m saying this while also fully acknowledging that many jobs just wouldn’t allow for this, again, the system is broken if we can’t really have the time to take care of the children we have!)

The main character does indeed go on an inner journey, re-discovering her wild side and the fact that she’s still who she was before having her child, deep down. Which was fun, and interesting (and again, I was wondering why she was the one doing all this inner-work? What about her husband? Shouldn’t they both be rethinking family systems?)

Now, what really killed any empathy I was feeling for this main character was (SPOILERS ahead) the strange and somehow ridiculous hatred she had for the family cat. Like, she didn’t hate her husband (often oblivious to the fact that she had literally no chance to rest while he could be on a work trip and still find time to watch a film, or game, or simply chill during the evenings) or her kid. But that cat? She absolutely despised her. And… she ends up killing her (the cat) in quite a graphic manner. Nope. I’m sorry, animal violence is something I despise. And a character I’m supposed to like is killing their cat? She just seemed repugnant to me after that (it doesn’t help that I have two cats I absolutely adore), and I just couldn’t care for her. This is a very personal thing, because I know killing the cat is part of the horror elements of this book, and I know it’s perhaps supposed to symbolise how this character refuses to care for another living thing. But it just didn’t work for me.

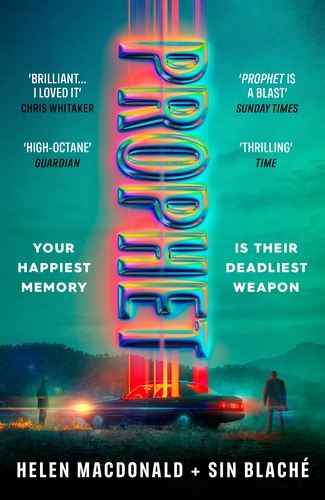

Prophet by Helen McDonald and Sin Blanché

Another book I read so eagerly and I really, really wanted to love… but I didn’t. I’m not sure why it was because it had all the elements of a book I should have loved (a sci-fi thriller with David Lynch vibes, lots of gay feelings between its two male protagonists, some horror).

I just didn’t connect with the characters, and I can’t really put my finger on why. The speculative element was also underexplained and underplayed, in my opinion. The first third of the book – the set up, in which we get introduced to this mysterious company that is weaponising the feeling of nostalgia – was great, but to me it just went downhill from there. The villains seemed quite stereotypical and underdeveloped as well, and I just felt like I knew how things would unfold (and I was right). The ending did redeem a bit of this thought, and I think there were very interesting ways in which this book negotiated ideas around nostalgia, trauma and family.

I’m sad I didn’t like it, even though it was an enjoyable read, and I would still recommend it because I can see people connecting with it.

Sensible Footwear by Kate Charlesworth

A great graphic novel all about queer history in the UK – alternating with Charlesworth’s own experience as a lesbian woman from childhood to her current age. I really, really liked this, and I felt it helped me learn a lot of the queer history of the country I’m living in, which I didn’t know. Charlesworth’s story was also really enjoyable, especially her relationship with her mother, who struggles with accepting her daughter’s queerness. It seems to me that anyone who loves Alison Bechdel (also a master in creating this hybrid memoir) would love Kateb Charlesworth’s work, and I can definitely recommend it.