Motherhood by Sheila Heti

I’ve wanted to read this book for a long time, so I jumped in glee when I discovered my library had the audiobook. It is narrated by the author (which is always enjoyable) so I borrowed it as quickly as I could. I listened to it in a few days (it’s a short one) through the darkness and rain of early December in the north.

I loved it and hated it – this was one book to inspire lots of feelings in me, often contradictory. I found the author’s voice annoying yet compelling. She narrates this book using, partly, the I-ching – she asks questions to it as if she was speaking to a god of sorts, or the universe, or a superior intelligence. This is amusing and strange – because, of course, she always tries to make sense of the answers she gets, which sound serene, loving, rarely random.

In this book, the author asks herself a question many child-free women in their late thirties are tortured by – should I have children? Why or why not? The author is in a stable (although somehow tumultuous) relationship with a man. She doesn’t seem to have any financial needs. She has a fruitful and respected writing career. This is, perhaps, what annoyed me (and this annoyance is purely subjective,). She seemed to have it all in life (a house in Toronto, no less, a partner, a job in which she gets to exercise her talents) so a part of me wanted to scream yes, yes, of course you could have a child if you wanted to, why not? Although of course that is precisely what worries Heti – altering this equilibrium, this life that is perhaps exactly what she wants (a life that comes with good things and bad things, sure, but feels as it should be). There’s a lot of focus on her partner – on the relationship they have, on their tensions and their issues and their small rows. At times it seemed to me she was too obsessed by this man, wanting to be loved by him and staying in the relationship no matter what. It all felt a bit too cisgender and heteronormative to me – like a woman needs to have a man and feel secure and safe in a relationship with him to truly be. (This is, again, a subjective observation from my part, that probably is more linked to my own experiences as a reader than to the text itself.) It’s also worth mentioning that Heti’s partner already has a child from a previous relationship and he doesn’t seem to have any interest in becoming a father again. Heti’s female friends, on the other hand, are having children (most of them are of a similar age to her, in their late thirties) and most of them are encouraging her to follow suit. Even then, Heti sees the huge impact children are having on their lives and she worries that this is something she doesn’t want for herself.

Now, this book also dwells into Heti’s own familial history, which, I have to say, was definitely my favourite part of the book. She writes about her grandparents and about her parents – about the ways they were brought up and how they formed families themselves, first in Europe and then in Canada. Heti’s upbringing is perhaps uncommon: her mother was a doctor, so she was busy studying and then working while she had children, so Heti’s father was the one who spent more time taking care of her and her brother when they were young. Heti confesses to feel some resentment towards her mother because of this, and to me, it seemed that this experience meant she felt closer to her father than to her mother, at least as she was growing up. However, this memoir already shows some interesting links between Heti and her own mother: they are both focused on their careers, and this (and not the labour of care) is the most important thing to them. They both too suffer from depression – Heti remembers her mother’s crisis when she was a child as she analyses her own as she wonders if she’s fit to become a parent.

Ultimately, this book is written beautifully – there is no doubt that Heti is extremely good at what she does. And I found the ending really touching – how Heti connects her grandmother’s story and her mother’s story to her own and she realises that she can still pass down her family legacy through other means (the work she does) even if she chooses not have children. I know before I was writing about this book feeling very cishet to me (and at points I wanted to shout at Heti please, do consider other ways of creating a family, ways that go beyond heteronormativity, you don’t have to do this on your own only because you are a woman… etc.) But there was something really powerful, refreshing and brave in Heti’s questioning of the idea of legacy – how, for men, they invest a lot of time on creating a legacy that has to do with the work they do or what they create, and they are respected for that – so why can’t women choose that path too without feeling ashamed or less than?

The Reformatory by Tananarive Due

One of the best horror books I’ve ever read. It has the perfect blend of history and fantasy and its most gruesome and uncomfortable parts are those in which the horror is perpetrated by real humans like you and I. And yet, this is a book that somehow, despite its very dark themes of violence, racism and death, manages to be somehow hopeful without being less harsh or thought-provoking.

The story follows Robert, a Black twelve-year-old 1950’s Florida who gets sent to a correctional after kicking his much older white neighbour. Robert is the son of a man who’s been fighting for social justice and equality in the small (fictional) town of Gracetown – because of this he had to escape to Chicago to avoid being murdered by the KKK. Robert’s mother has died of cancer, which still haunts him and his older sister, Gloria.

When Robert gets sent to the reformatory, the novel splits to focus on two different narrators. On the one hand, Robert struggles to survive in a place where Black and white children are treated with extreme cruelty and forced to turn on each other. The reformatory’s warden is a particularly evil and sadistic character who clearly enjoys torturing the children he’s meant to educate and ‘reform’. He is, perhaps, also, the most conventional villain in the story (although not the least chilling or disturbing because of that). Yet the novel makes it clear that the reformatory is hell on earth because those working under the warden’s orders don’t or won’t stand up against him even though they know (and sometimes even participate in) his horrifying practices. In the reformatory, Robert tries to make friends and soon discovers that his supernatural ability to see ghosts (many of them spectres from the children who died there) will make his stay there even more dangerous.

The other part of the novel focuses on Gloria, Robert’s sister. Despite having literally everything against her (and she’s not even an adult yet) she’s set in freeing her brother – as she knows he may not survive his six-month sentence in the reformatory. I can see how some readers could feel that Gloria’s sections are less gripping or interesting because they don’t have the stark horror ambiance of Robert’s chapters. But they were my favourite ones. For one, I found her perspective very moving and intense – this is a story of two siblings in very difficult circumstances who keep going because the love they have for each other. Gloria’s narrative also brilliantly encapsulated the real terror of living in a society in which you are constantly under surveillance and any wrong move at the wrong time can mean death. For example, even though the speed limit in Gracetown is 35 miles Black people living there know that going above 25 will mean being stopped by the sheriff – and that can have very bad consequences. One of the most terrifying scenes in the novel involves Gloria and her old aunt being stopped by the police in the car – there’s a real sense that they could be killed and their bodies disposed of and there wouldn’t be any consequences for the perpetrators of such a crime. There’s another chilling scene in which a group of Black lawyers try to argue Robert’s case with the judge who sentenced him – to be almost immediately dismissed. The legal system is not only shown to be biased but irremediably broken.

This was an incredibly visual book too – some scenes in Robert’s section were some of the most revolting I have read in horror for a long time. For the last fifty pages or so of the novel I was literally glued to it, shaking, fearing for its characters. I haven’t felt so involved in a book for a long time.

At the end of the novel, there’s an author’s note in which Due explains that her own uncle died as a child in a reformatory similar to the one depicted in the novel. A lot of the research she did for this novel involved recuperating the memory and history of a horrible place. This was chilling to read – but also powerful. Due is a talented writer, and she’s using her skill to recover her family’s memory and make sure that we don’t forget that places and injustices such as this have existed not that long ago. This what horror does best, in my opinion, it forces us to look at harsh truths, it asks us to empathise with very difficult experiences and see darkness that many would prefer to ignore or forget.

Intermezzo by Sally Rooney

I was very curious about the new Sally Rooney’s book and finally got my hands on it. This is her first narrated almost exclusively through the perspective of two male characters – brothers Ivan and Peter, who have recently lost their father and are grieving in very different ways.

Something interesting about this novel is that, actually, there’s no much about the father himself or the specifics of the relationship he had with his sons. Instead, the novel focuses almost exclusively on Ivan and Peter’s romantic and sexual relationships in the aftermath of their father’s death. Peter, the older brother and a barrister by trade, finds himself in a casual relationship with twenty-three year-old Naomi. He’s still very much in love with his ex-girlfriend Sylvia, who, after being in an accident, is in intense physical pain and can’t have sex anymore (which seems to be the main reason she broke up with Peter in the first place). On the other hand, Ivan, the younger brother, falls in love with Margaret, a thirty-six year-old woman thirteen years his senior. This is his first serious relationship – and when he tells Peter the good news, his older brother is critical and worried. Peter is convinced that Margaret must be ‘crazy’ to fall in love with someone like Ivan (it’s implied that Ivan, who is a chess prodigy, is also on the autistic spectrum). Peter is also worried that Margaret may be taking advantage of Ivan’s inexperience with romantic relationship. Oh, and yes, Peter is kind of forgetting that he is himself in an age gap relationship with Naomi, which is a tad ironic.

I enjoyed reading this novel. A lot. It actually only took me three days to finish it (and it’s not a small book). I was thoroughly entertained by the romantic drama of the brothers. This book, like all the other Rooney’s books I’ve read, is, fundamentally, about miscommunication. Ivan and Peter love each other, yet they struggle to communicate with each other in an effective way to the point that Peter secretly considers his brother an intel and Ivan thinks that Peter doesn’t care about him. Which is a real human struggle – not being able to understand how we feel, not being able to ask for help or to communicate our true desires. Sometimes it’s because we are afraid or because we haven’t even been given the tools to do so. My favourite scene in the novel (spoilers ahead) is the encounter between the two brothers in which Peter confesses how sad, lonely and disappointed he felt when Ivan and his father refused to acknowledge the deep depression he was in right after Sylvia’s accident and their subsequent rupture. There’s a particular hurting memory for Peter – a night in which sixteen-year-old Ivan found him crying in the family’s kitchen at night but instead of asking him what was going on or consoling him he simply went away. Ivan remembers this too very well – but at that time he wasn’t feeling disinterest or rejection (which is how Peter interpreted his reaction). He was scared because he didn’t know how to deal with his older brother’s pain and vulnerability.

I was amused by some of the epiphanies these characters have throughout the books (apart from Peter and Ivan, Margaret is also a narrator in this story). I loved that Peter finally accepted that non-monogamy may be a natural path for him. And that Ivan always trusted his own feelings for Margaret. And that Ivan’s dog, Alexei, was finally rescued from Peter and Ivan’s difficult mother who definitely wasn’t a good pet owner.

There also some interesting philosophical and linguistic challenges and questions addressed in this work. And, according to the author’s note at the end, she has also used many quotes from other writers and has put them in her characters’ dialogue. This is really interesting as when I went through the credits for these quotes I found a few sentences I had loved in the novel (and that I had thought were Rooney’s!) I’ve never done something like this an author – giving my characters specific sentences written by someone else – and I find the practice intriguing. Also, Rooney has said in interviews that the particular syntax in some of Peter’s extracts in the novel is directly influenced by her reading of Ulysses by James Joice…

Niñapájaroglaciar (Girlbirdglacier) by Mariana Matija

I heard great things about this book a while ago, so I was really excited to find it in a bookshop in Bilbao when I was on holidays. It’s a collection of essays by the Colombian author Mariana Matija focused on her relationship with nature and animals. What I loved the most about this collection was about how genuine this love felt – love for the plants, the animals and, by extent, the humans Matija has grown up with.

My favourite sections of this book were her experiences of travelling through different settings. There’s a particular intense passage that narrates her adventure climbing a dying tropical glacier in Colombia. I had no idea that tropical glaciers are a thing – although, of course, considering that the Andes run through most Central and South America, this makes sense. I have to say that I grieved with Matija about their disappearance. Only because of this I think Matija’s writing is important – as it celebrates but also asks as to consider and care about a fragile natural world that is not immune to human destruction. Another interesting passage is her essay about her obsession with Iceland (which stars after she’s introduced to Björk’s music). When she visits the country she starts drawing parallels with the somehow similar geography in her native Colombia, which includes glaciers and volcanoes too.

Another striking essay is about the concept of extinction – that she examines through the history of the dodo and the thylacine (a marsupial from the island of Tasmania). There’s a connection in Matija’s writing between mental illness and the destruction of the natural world – who can keep sane when they see nature dying and decaying around them because of human exploitation? Who gets to decimate natural resources to benefit the interests of those who don’t even live near them?

At times, the writing in this book seemed a tad repetitive – and some ideas kept appearing in very similar ways throughout different essays. That said, I enjoyed this collection overall. Matija’s writing about her pets, for example, was particularly touching and sad as it celebrated the relationships humans can have with other species, which, of course, are fundamental if we want people to feel a connection with the natural world.

The Great Farce by Michael Graziano

One of the strangest, most disgusting novellas I have ever read. A great premise: as it starts with a narrator who finds himself trapped in an extremely tight box in total darkness with other two people, a man and a woman. We don’t know how he ended up there, or why he doesn’t die even though he can’t even sit down and has to stay on his feet. If you think this already sounds strange – the rest only gets stranger.

This is a claustrophobic and raw portrayal of a character experiencing a hellish situation. When Henry (the name he ends up giving himself, because he can’t remember having a name or even a life before the box) finally escapes he finds himself in a cruel labyrinth of caves filled to the brim with other humans and animals who seem to be condemned to stay there for all eternity. Water and food are scarce and can only be obtained by the strongest, often through violence. Because everyone is struggling to survive, there’s no time to rest or to establish any sort of social relationships. When Henry finally manages to escape this second setting (thanks to his observing nature and to his creativity, I should add) he access a place where he has absolute control over food and water – but he’s still every bit as miserable, as he finds himself alone. Paradoxically, he still misses his life in the tight box and the people he shared it with at the beginning of the story and even resolves to leave his new found ‘paradise’ to find them.

I read this short novel in one setting and couldn’t stop thinking about it for a few days. The whole book reads like an allegory for something else – the scenes described are raw, but also surreal. I think every reader can see in this story different things. At this time, it seemed to me a metaphor for life and the different stages one goes through. Life in the tight box is perhaps childhood: a time where we feel we belong to a family (if we are lucky enough, that is) even though this is also a time where we have to obey the adults’ rules and we don’t have control over many things. The second stage is adulthood and the rat race. We are launched into this world in which we need to survive at all costs – which often means focusing on working and earning money to the detriment of our humanity. I’m talking here about bullshit jobs, unfair social systems and a world that demands that we enact a constant state of production if we want to be ‘proper’ members of society. The third stage is enlightenment and success – Henry literally gets to see how the feeding system of ‘hell’ works and he has absolute control over it. Yet, this doesn’t bring him happiness or fulfilment. He misses his friends. I think this is because human experience is rich when we get to share it with others.

This Part is Silent by S J Kim

I was very curious about this collection of essays as it touches on a few topics that feel very close to me: writing, migration, multilingualism and academia. It didn’t disappoint, and it’s beautifully written as well. I wasn’t ready for it to break my heart, and it did, and it was painful but also cathartic.

I was expecting to read about the experience of dislocation and living between languages and cultures. Kim touches on her personal experience as a person who lived in Korea but moved to the South of the United States with her family when she was only seven years old. What I love about this book is that Kim uses Korean often to describe a few things, and the book never comes with a translation of a glossary. I’m so interested in this kind of hybrid literature that unashamedly blends in different languages and I thin many of us in the world are bilingual and very interested in these kind of multilingual texts. I don’t speak Korean, but I do speak Japanese, which also uses characters to write and a syllabary, so I found myself looking at Korean in this book trying to recognise which characters were the same and see if I could intuit what they meant.

Now, what broke my heart was the honesty and bravery in which this book addresses the toxicity and the nonsense of the academic experience (specially as someone who teaches Creative Writing or, by extent, a subject from the Arts and the Humanities) in the United Kingdom right now. There were a few parts when Kim was talking about painful experiences where I fell so recognised I was almost in tears. It was so important for me to read these parts, because academia’s constant insistence to prove our value and our expertise above everyone else makes us all feel so isolated, frustrated and unhappy. I talked about this when I was interviewed by the British Academy in their podcast, but I don’t think that feeling the pressure to be ‘the best’ at all times or having to prove this constantly really supports important research that will be, in turn, meaningful for society. For example, Kim discusses in her book the experience of having to submit work to REF, the ‘research excellence framework’ in the UK all universities must participate in. She writes about the difficulty (and ridicule) of having to contextualise her own creative work by writing an abstract, a methodology, research outputs and the such (this is a modus operandi that comes directly from the sciences, which, as one can imagine, doesn’t really translate into a piece of creative writing). This reminded me of my own experience of trying to do the same, which left me feeling inadequate and, quite honestly, like I wasn’t ‘a real’ academic. But also, when I think about literature and writers I know how valuable their work is to me and many more people in the world (Kim’s book, for example, is a clear proof of this). Why is not this sort of creative research honoured, respected and valued for what it is? Why shall be keep proving on and on that our research is ‘useful’ and ‘utilitarian’ in very narrow, financial terms? Why aren’t social values being considered? Kim’s bravery to speak about the toxic burnout culture that initiatives such as REF generate is refreshing and powerful. I also felt very seen when she goes into the difficulty of being a junior member of staff at a university on a permanent, full-time – trying to find time to do research with heavy teaching loads and other administrative and pastoral demands we can hardly cope with. I know I will be coming back to this book when I feel alone and undervalued at my job (which is happening quite often these days). This book also reminds me that we can all do something to fight against the blatant racism and inequalities within academia. Every effort, no matter how small, matters, and some systems need to be dismantled, challenged and questioned so they can change.

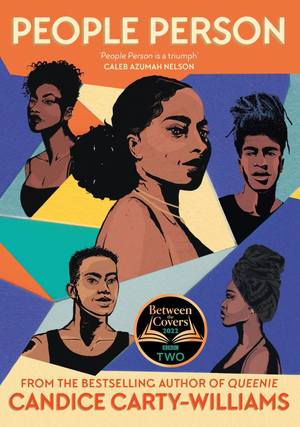

People Person by Candice Carty-Williams

I read Queenie from the same author last year and loved it, so I was eager to start with this one. This is a character-driven book that had me hooked from the very first pages. It follows Dimple and her four siblings, Nikisha, Lizzie, Danny and Prynce, who all have the same absent father but different mothers. The book starts with a brilliant scene in which their father. Cyril, wakes up one morning and gets on his gold jeep. He’s on a good mood and has decided he’s going to take all his five children for ice-cream, which is quite remarkable, as usually he’s not present in their lives as he has, pretty much, abandoned them all emotionally and financially. It is an awkward encounter as Nikisha, the eldest, who is already nineteen years old and his children have never met each other before (but have heard about their father adventures, affairs and relationships with other women).

After that, the novel makes a fifteen year jump and focuses mainly on Dimple. From all Cyril’s children, she’s the most forgiving and the ones who misses her father most openly. When something horrible and unexpected happens in her life, she doesn’t know how to call for help and ends up getting in touch back with her estranged siblings our of sheer necessity. With all the siblings involved in something quite dark, they are all forced to spend time together. And, almost instantly, bonds start to form.

I loved this book. First of all, it’s written in such an engaging style. Also, I really enjoyed reading a book primarily focused on sibling relationships – the good, the bad and the ugly – in contemporary London. Dimple is such an interesting character – she’s trying to make a living as a YouTuber while coming to terms with an absent father and a mother who is always asking for attention. She has many flaws – she’s very insecure of herself, and is not the best at having relationships with other people. The title of then novel makes reference to both Dimple and her father Cyril. Cyril is always seen by others as a ‘people person’ with his friendly, charming demeanour. Dimple, on the other hand, is criticised by her younger sibling Prynce as someone who’s not really a ‘people person’ because of her shyness and general awkwardness when she’s in a social situation. Yet the novel challenges both these notions. Of course Cyril is charismatic (even I found myself liking his character) but he is, in reality, very dismissive and unkind to those close to him. On the other hand, Dimple is someone who is genuinely seeking connection with others and she’s prepared to risk her feelings and get vulnerable to form bonds with the people she cares about, such as her siblings.

This book had a few over the top twists and turns – but overall it remained honest and touching at its core, which I really admired. I think it was at its best when Carey-Williams focuses on the siblings and their back stories. I wouldn’t have minded reading more about Danny and Nikisha, for example, who don’t end up getting that much time in the novel. To be fair, this could have been the first book in a family saga.

I also was very interested in reading a book about characters struggling with a very problematic parent who they love, or hate, but can’t really get rid of.