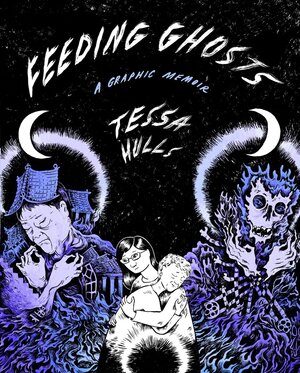

Feeding Ghosts by Tessa Hulls

This is one of the best graphic novels I have ever read – and also, one of the hardest. Ever. Pretty much like Palestine by Joe Sacco and Maus by Art Spiegel (which I wholeheartedly recommend), I found myself having to put the book down to process it. This couldn’t be done in one sitting. But it is extremely good, a thought-provoking, and it encompasses a lot, from family dynamics to mental health to art and purpose to very complex (and often terrifying) historical events from twentieth-century China.

This is also a graphic novel I was eagerly waiting for from the moment I heard it had won a Pulitzer award. I’m also very interested in historical memory and familial and collective memory – how we inherit the stories from our ancestors, sometimes even without knowing them first hand, as it is the case in this particular graphic novel.

This is also Hull’s first long-form work (although she has excellent short comics published in different places, you can see all those listed in her website). It is, of course, pretty impressive. I have listened to a lot of interviews with the author in which she swears this will be the only graphic novel she’ll ever draw. She says it’s done. I’m saddened, because I’d read every graphic novel she’d produce – but also, I sort of understand. I can see why working on this story would take an extraordinary amount of energy – both physically and mentally.

Hull’s style reminds me a lot of Craig Thompson’s in Blankets – another of my favourites. But I have to say that Hull’s ambition expands from the personal to the collective. This is not only Hull’s story but the story of her mother, Rose, and her grandmother, Sun Yi. This is also the story of China after the Cultural Revolution. The story of those children who were half-Chinese and half-European and grew up in Hong Kong. The story of those children who were half-Chinese, half-european and grew up as children of immigrants in the States. There are a lot of layers.

I don’t know much about Chinese history, and this was a very fascinating insight into it through the familial history of Hull’s mother and grandmother. One of the most terrifying things was to see the development of a regime that was very much authoritarian (even though masked as a communist one). Particularly chilling were Hull’s descriptions of the psychological torture ‘enemies of the state’ (the so-called ‘thought reform) went through – such as Sun Yi, Hull’s grandmother. Through this kind of torture, individuals were asked to write and rewrite their own confessions again and again until they started struggling to differentiate what was real and what had been made up. After that, they were forced to come back to the police to rewrite detailed weekly accounts of everything they had been doing during a week, to then have all of these details scrutinised and often questioned. Going through this frequently made people withdraw from others (terrified that they would have to give account of these transactions too) and stop trusting even their own memories. Can you imagine feeling like an unreliable narrator of your own life, to the point where you feel you can’t even trust yourself with anything?

The story also covers Rose’s life (Hull’s mother) as a child born to a single mother in Shanghai who is brought up in Hong Kong as a child of the ‘Eurasian’ community (since her mother is Chinese and her father, who left China without meeting her, is Swiss). As Sun Yi’s mental health disintegrates and she has to be hospitalised several times, Rose becomes her mother’s sole carer when she’s barely a child. This is a highly dependent relationship they have had for all their lives, as Sun Yi is declared mentally unstable (and needs to be heavily medicated to function), and Rose ends up taking care of her in the States once she establishes herself there after completing her university studies.

This is also the story of Hulls growing up in a family with lots of secrets and trauma that she inherits just by being born into it. Firstly, when Hulls is a child, she’s scared of her grandmother – Sun Yi doesn’t speak English and Hulls doesn’t speak Chinese, so they can’t communicate. She’s also scared by her grandmother’s multiple breakdowns and fragile mental state. At the same time, Hull’s relationship with her own mother is very complicated – secretly, Rose is worried that Hulls may have inherited Sun Yi’s mental health issues and takes any form of rejection or detachment from her daughter as proof of that.

It’s only years after Hulls leaves the parental home (suffocated by the relationship with her mother, which has become strained and difficult) that she starts discovering, little by little, her grandmother’s complex and fascinating story, years after she’s died. For example, she gets to know that Sun Yi was a journalist and a single mother who had to bring up a baby all on her own after the father left them. Sun Yi was also the author of a very famous memoir about her time living in Communist Shanghai under terrible repression and her experience of having to escape to Hong Kong with her child on a boat as refugees.

From here, Hulls starts a fascinating investigation into her family – and, of course, Chinese history – that takes her many years. She starts learning Mandarin and acquires funding to have her grandmother’s memoir, Eight Years in Red Shanghai, translated into English. Through the years (this graphic novel took Hull ten years to write), the author starts unravelling her grandmother and mother’s complex history of trauma and abuse. In the process, she gets close to her mother as well, as Rose finally opens up and shares with her her own version of the events she can still remember. Eventually, this research and writing is also a healing process of understanding and giving voice to all those familial ghosts that haunt us. It’s a story about history and culture – the impact they have on us, even before we are born.

This is a book that I will read more than once, for sure, as it’s so complex and layered that I’m sure I may have missed many things. It was absolutely splendid and left me in awe. A hard recommendation!

Doppelganger by Naomi Klein

Another hard read, albeit for very different reasons. I’m realising that July was a difficult month for me health-wise wise and somehow I gravitated towards really dark books.

I had started listening to Doppelganger as an audio book, which is narrated by the author, but somehow I couldn’t get into it, because there was a lot of information I knew I was missing. So I decided to read it instead, which proved to be the right choice.

The story is, initially, simple but fascinating. Historically, Naomi Klein has been confused with Naomi Wolf. Both authors started writing somehow similar topics. They were both leftist feminists, they looked fairly similar, and they were both living in the States. Until 2020, when Wolf suddenly makes a ‘U’ turn, thinking-wise, and starts spreading misinformation relating to Covid-19, vaccines, and even 5G technology. She also becomes a regular on podcasts hosted by Trump supporters, which promote different conspiracy theories.

Wolf’s downfall as a literary genius – her book, The Beauty Myth, was hailed as one of the best feminist books ever written – already started in 2019, when it was discovered that her book Outrages: Sex, Censorship, and the Criminalization of Love, based on her 2015’s Oxford PhD thesis, contained key research errors. Specifically, she had misunderstood the term ‘death recorded’ in her archival research as meaning that a convict had been executed when in reality, it means they have been pardoned or had their sentence commuted.

From this, Klein starts pondering about doppelgängers and doubles – basically looking for every ‘shadow side’ our societies (and ourselves) may have and what that means. There are lots of topics covered here. For example, Klein writes about health and the health industry, vaccines, medicines, and the idea of ‘clean eating’ or having a ‘clean body’ which thrives by avoiding all sorts of toxins, including medicines and vaccines.

She also writes about authoritarian regimes, fascism, and language. How some fascist politicians have started using language in really interesting ways, defining themselves as the ‘oppressed’ in a system that is trying to challenge them. If the fascist is calling you ‘fascist’, then the meaning of the word ‘fascism’ starts getting diluted, and everyone starts getting really confused about what fascism really is. Are they right? Are we right? (Once again, two sides, pitted against each other).

There’s also a brilliant chapter about parenthood, vaccines, and the autism spectrum. It covers the history of autism diagnosis and the Austrian paediatrician Johann Friedrich Karl Asperger. At the beginning of his career, it seemed he was keen on protecting neurodiverse children – yet, his research advances also developed a sort of ‘scale’ in which said children were considered ‘smart and useful’ or ‘not useful’, the latter justifying their killing during the Nazi regime. Klein also talks about her personal experience having a neurodiverse child – and the importance of letting go of those expectations that we may have on our children as extensions of ourselves. Children are their own people, and pretending that we can train them to fit whichever social ideal we have in mind could be incredibly damaging. (I was terrified to learn, for example, that apparently some people believe they can train their children ‘not to be autistic’).

My favourite chapters were the ones about history, society, and the double meaning of language and concepts. It truly explained the power of myth and words, which I recognised from my reading of books such as 1984 by George Orwell, but also my research into harrowing political moments such as the Spanish Civil War.

This book also helped me understand why some would firmly believe in some conspiracy theories. I have someone very close to me who was completely changed by Covid-19 to the point where now we share very different versions of the world (and terrifyingly so). This was one of the main reasons I read this book – I wanted to get closer to them, understand why. This book hasn’t solved any problems for me, but it has made me feel closer to this person. I especially liked this quote below on conspiracy theories and why they make so much sense in the world we live in today:

‘What is this strange drive to reveal the nonhidden? Maybe it’s that, in liberal democracies that still pay lip service to social equality (or at least “equity”), there is something profoundly unsatisfying about how open our global elites are about the power they believe they have a right to wield over the rest of us. The mechanics of oligarchy are not hidden; they are flaunted with a level of pride that actively humiliates their spectators. Billionaires, heads of state. A-list celebrities, journalists. and members of various royal families gather every year at the World Economic Forum in Davos Switzerland… they take up the mantle of solving the world’s problems – climate breakdown, infectious diseases, hunger – with no mandate and no public involvement and, most notably, no shame about their own central roles in creating and sustaining these crises.

Knowing that this kind of unmasked plutocracy can take root in democratic societies without so much as an effort to hide it is like being forced to watch your spouse cheat on you when that is not your kind of kink. Maybe we should see conspiracy culture – with its theatre of uncovering things that are not hidden – as some sort of twisted lunge for self-respect.’

(p. 240)

‘There is something else that seems to be feeling conspiracy culture now. The extreme consolidation in the corporate world over the past three decades has produced a playing field so rigged against consumers that pursuing the basics of life can feel like navigating a never-ending series of scams. It’s as if everyone is trying to trick us in the fine print of pages and pages of terms of service agreement they know we will never read. The black box is not just the algorithms running our communication networks – almost everything is a black box, an opaque system hiding something else. The housing market isn’t about homes; it’s about hedge funds and speculators. Universities aren’t about education; they are about turning young people into lifelong debtors. Long-term care facilities aren’t about care; they’re about draining our elders the last years of life and real estate plays. Many news sites aren’t about news; they are about tricking us into clicking on autoplaying ads and advertorials that eat up the bottom half of nearly every site. Nothing is as it seems. This kind of predatory, extractive capitalism necessarily breeds mistrust and paranoia. In this context, is not surprising that QAnon, a conspiracy theory that tells of elites harvesting the young for their lifeblood (adrenochrome), has gone viral. Elites are sucking us dry – our money, our labour, our time, our data. So dry that large parts of our planet are beginning to spontaneously combust. The Davos elite aren’t eating our children, but they are eating our children’s futures, and that is plenty bad.’

(pp. 242-243)

The final chapters of the book on history are also brilliant, specially when it comes to Klein’s reflection on colonialism. This particular quote is related to the Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck – creator of the four-part HBO miniseries Exterminate All the Brutes inspired by a book of the same title by the Swedish writer Sven Lindqvist, published in 1992.

What I did no expect to discover is that Peck’s opus was a doppelganger story. His thesis is that the dominant story we tell about Hitler and the Holocaust – which treats that frenzy of death as so extreme that it is without historical precedents or antecedents – is flat wrong. Peck argues instead that the Holocaust was an intensified and compacted expression of the same violent criminal ideology that ravaged other other continents at other times. (…)

The story Peck an Lindqvist tell begins not in the Americas but in Europe in the centuries leading up to the Spanish Inquisition and the burning at the stake and the bloody expulsions of Jews and Muslims. Then it crosses the Atlantic and plays out on a vastly larger scale in the genocide of Native Americas, as well as the so-called Scramble for Africa, before looping back to Europe during the Holocaust. This challenges how the story of the Second World War is so often told: as one of heroic anti-fascist Allies united against the monstrous Nazis. Certainly, defeating Hitler and freeing the camps, however belatedly, was the most righteous victory of the modern age. Complicating this story is the fact that Hitler spoke and wrote extensively about the many ways in which he drew inspiration for his genocidal regime from British colonialism and from the various structures of racial hierarchy pioneered inside North America.

(pp. 268-269)

The last few pages of the book do feature a bit of optimism (very much needed at that point, this is a hard read), and this quotes spoke to me:

This is the one overarching message I choose to take at the end of my doppelganger journey: time to loosen the grip on various forms of proprietary pain and selfhood, and reach toward many different forms of possible connection and kin, toward anyone who shares a desire to confront the forces of annihilation and extermination and their mindsets of purity and perfectionism… Up against oligarchy, all we have is the power latent in our capacity to unite. Race, gender, sexual orientation, class, and nationality shape our distinct needs, experiences and historical debts, We must hold on to those realities and build on a shared interest in challenging concentrated power and wealth, while constructing new structures that are infinitely more fair, and more fun.

Most tasks are easier than done. In the case of coming together across seemingly intractable barriers, however, the reverse may be true: this one is easier done than said. Stuck in the realm of words, we will never run out of reasons to fracture. But when we take action to change material circumstances – wether trying to unionize our workplaces, or halt evictions, or free political prisoners, or build alternatives to policing, or stop a pipeline, or gent an insurgent candidate elected – those tensions do not disappear, but they are often balanced by the recognition of shared interests, the pleasures of camaraderie, and, occasionally, the thrill of victory.

(pp. 330-331)

This is the power of collective organizing; it expands the sense of the possible by expanding the possible “we”. It persuades participants that, contrary to what they have been told, their pain is not the result of a failure of character, or insufficient hard work. Rather, it is the consequence of economic and social systems precisely designed to produce cruel outcomes, systems that can be changed if only people drop the shame and unite toward a shared goal. When enough people start believing that, it is an awakening in the truest sense of the word – a new group identity is constructed in real time, one wider and more spacious than what existed before.

(p. 332)

And finally, a quote that explains the concept of ‘Shadow Lands’ which Klein (who is Canadian but has lived in the States for long periods of her life) uses in her book:

I’ve written about settler colonialism in these pages as a violent and annihilator practice, which it is. It also strikes me that it must have been frightening for the early European settlers of these lands to come to places they did not know or understand, places that, for them, had no stories, no myths, no sacredness. One of the ways they attempted ton orient themselves was by giving these places that were so new to them the names of other, more familiar places, or giving the new places their own names… Graudually, the real names of these places are becoming visible, the names behind and beneath those names. Now the green road signs along the highway often have two names: they will read TS’UKW’UM (WILSON CREEK) or XWESAM (ROBERTS CREEK); the two words occupy the same space. It makes for a challenging twining, holding in one’s consciousness the names colonists gave places they barely knew and the names the shíshálh Nation had and never stopped having for these same places. The signs invite those of us who are not Indigenous to have a double consciousness – to remember that we are living in a nation that imposed itself onto other nations and tried to relegate those nations – their people, languages, cultures, ways of knowing – to the Shadow Lands.

(p. 341)

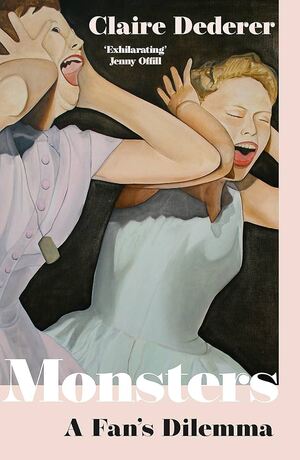

Monsters: a fan’s dilemma by Claire Dederer

To finish the month, another hard book. I’d been after this one for a while – and I was very happy to find it in my library. I’ve been teaching Creative Writing for nine years now, and this is a question that always comes up in my teaching with my students. What’s the relationship between the artist and the art they produce? Do we stop engaging with the writing of someone who is truly awful? And also, one of my favourites, as a horror writer, if someone writes from the point of view of a monster, does that make them a monster? This book was surprisingly enjoyable to read. I was expecting something a bit more dry perhaps, a bit more academic, but this is not at all Dederer’s style. She writes in a very enjoyable way, often blending in bits of memoir with her very thorough research. The book opens up with the author’s confession that they love Polanski’s movies and they still watch them regularly, even though Polanski is a man who has done horrible things. Dederer then goes to use a metaphor – thinking about a work of art ‘stained’ – like a beautiful rug, or tapestry, or painting – by what we know about its author. I think that’s an interesting analogy – the work of art can still be as good and we can enjoy it, but it’s not the same as the stain has altered something about it permanently.

Something I liked about this book was how Dederer doesn’t judge – she recognises that whatever background we come from may have a direct influence on how we decide to engage with art – and this means that we’ll all have different experiences and justifications as to why we want to engage or not with an artist’s work. For example, someone who may have been abused as a child may refuse to engage with Polanski’s work in any way, shape, or form, whereas for Dederer this is still possible. It also depends on when you came into contact with a specific work at some specific time – for example, if that particular book or that particular music album brought you solace during harrowing personal times as a queer person, you may find yourself still engaging with it beyond discovering that its author is homophobic – and so on.

One of the most interesting chapters was about the idea that you need to judge a piece of art ‘in its historical context’. That is, ‘forgiving’ an author for being sexist, misogynistic, homophobic, racist, xenophobic, etc, just because ‘everyone was like that at the time and they didn’t know any better’. Derderer is quick to remind us that human beings have always known better through time – some of them just choose to hate specific groups. (Say, there’s always been movements against discrimination all throughout time).

There’s also a chapter about perspectives – and about the current thinking that if you are a white man suddenly your perspective is being almost ‘cancelled’ in favour of other ‘more diverse’ perspectives (insert eye roll here, as this is an argument I’ve heard from many colleagues and students I’ve worked with through the years).

We are all bound by our perspectives.

Authoritative criticism believes in the myth of the objective response, a response entirely unshaped by feeling, emotion, subjectivity. A response free, in fact, of any kind of personal perspective. For the male critic, there’s no need to question that response because the work is made by someone like himself. Them work is transmitted from one type of artist (that is, male) to the same type of viewer (also male). The artist has an ideal audience; the audience has an ideal artist; the rest of us are outside of that dyad. Not excluded; but not of the dynamic.

Of course we can do the same: we can make art centred around our own experiences, and leave out the men who’ve been centralized for so long – and they still won’t understand that their point of view is non-central, one of many.

(…)

Monty Python’s Terry Gilliam responded [to this kind of criticism] vehemently, saying, “I no longer want to be a white male, I don’t want to be blamed for everything wrong in the world: I tell the world now I’ a black lesbian.” (…) Listen, I rather watch the Pythons than Gadsby any day of the week, but the point is this: None of these guys has the bandwidth to even entertain the idea that a woman’s or person of color’s point if view might be jus as “normal” as theirs, just as central. They seem incapable of understanding that theirs is not the universal point of view and that their own comedy has left people out. That exclusion is not necessarily a problem for me, it’s just a fact. As lifelong excluders, they shouldn’t use their own (ridiculous) feelings of exclusion as a critique of the work of people who look different from them.

(pp. 70-71)

But my favourite chapter – and one I’ll refer to in my teaching, as, being a horror writer myself and having written about some truly horrible characters through their perspectives – is the one about Nabokov and the infamous novel Lolita (which, I’ll admit, I haven’t red yet, but it’s definitely on my list after this).

The concept of the writer as a moral agent is something that keeps coming up whenever I teach – what do we do when characters do, think, or say racist, homophobic, or sexist things? Does that mean the writer approves of all of these things? Should art always strive to be good and moral?

Of course, as a horror writer, I think that good art can be about horrendous people. I’d go as far as to say that horror is about empathy and the exercise of it – it’s about confronting the monsters inside us or the societies we live in, so we can first come to terms with them and then think about ways we could challenge some inherently problematic status quo. Horror is about those left behind, about those who are often suppressed or preyed upon. (It shouldn’t come as a surprise that some of my favourite horror writers, Mariana Enríquez and Heather Parry, constantly engage with social issues and politics in their work.)

Here are Dederer thoughts on the ‘Lolita issue’:

‘We shouldn’t punish artists for their subject matter.

But we do. We punish artists for their subject matter all the time. Now more than ever. Could Lolila be published today? I doubt it. The story of a serial predator who grooms a young girl, abducts her, takes her on a cross-country road trip, rapes her every night and every morning too, and prevents her escape at every turn? And we only get his point of view? It’s impossible to know wether or not the book would be published now, but it’s easy to imagine an outraged reception.

(…)

To put it another way: why did Nabokov, possessor of one of the most beautiful and supple and just plain funny prose styles in the modern English language, spend so much time and energy on this asshole?

Maybe the answer can be found in the words of another asshole, Roman Polanski. In the klieg-light aftermath of his rape of thirteen-year-old Samantha Gailey, he said his desire to have sex with young girls was the most ordinary thing in the world. “I realise, if I have killed somebody, it wouldn’t have had so much appeal to the press, you see? But… fucking, you see, and the young girls. Judges want to fuck young girls. Juries want to fuck young girls – everyone wants to fuck young girls!

Polanski, of all people, has given us a piece of wisdom here: the desire to rape children is not so unusual. Why should Nabokov tell the story of Humbert? Because, as Polanski tells us, it’s an ordinary human story. It’s terrible and unthinkable and appalling and it happens all the time. That makes it fit subject matter for a writer.

(pp. 138-140)

The book finishes with some ideas on what to do next – and also an interesting critique of the power we may think we have (or the duty, even) as consumers:

‘I came to see the question “what do we do with the art of monstrous men?” in a new way. The initial thought of how to take responsibility is to boycott the art – the liberal solution of simply removing one’s money and one’s attention. But does that really make the difference?

To say someone else is consuming improperly implies that there’s a proper way to consume. And that’s not necessarily true.

(…)

Passing the problem on to the consumer is how capitalism works. A series of decisions is made – decisions that are not primarily concerned with ethics – and then the consumer is left to figure out how to respond, how to parse the correct and ethical way to behave. Michael Jackson is exploited, packaged, served, catered to, even as his behaviour becomes more and more erratic. The music industry doesn’t concern itself with the ethics involved; that’s left to us, caught in a cavacalde of emotions and responses as “I Want You Back” plays over the café speakers.

(…)

Art does have a special status – the experience of walking through a museum is different from, say, buying a screwdriver – but when we seek to solve its ethical dilemmas, we approach the problem in our role as consumers. An inherently corrupt role – because under capitalism, monstrousness applies to everyone. Am I a monster? I asked. And yes, we all are. Yes, I am.

(pp. 239-240)

And of course, this book also covers cancel culture. I found myself agreeing with the author here too – it seems way too easy to simply show our ‘goodness’ by cancelling some authors or celebrities. That’s a rather passive act whereas there are a lot of more powerful ways in which we could resist and challenge some of the problematic behaviours or attitudes these celebrities embody.

Condemnation of the canceled celebrity affirms the idea that there is some positive celebrity who does not have the stain of the canceled celebrity. The bad celebrity, once again, reinforces the idea of the good celebrity, a thing that doesn’t exist, because celebrities are not agents of morality, they’re reproducible images.

The fact is that our consumption, or lack thereof, of the work is essentially meaningless as an ethical gesture.

We are left with feelings. We are left with love. Our love for the art, a love that illuminates and magnifies our world. We love wether we want to or not – just as the stain happens, wether we want it or not.

(…)

In other words: There is not some correct answer. You are not responsible for finding it. Your feeling of responsibility is a shibboleth, a reinforcement of your tragically limited role as a consumer. There is no authority and there should be no authority. You are off the hook. You are inconsistent. You do not need to have a grand unified theory about what to do about Michael Jackson. You are a hypocrite, over and over. You love Annie Hall but you can barely stand to look at a painting by Picasso. You are not responsible for solving this unreconciled contradiction. (…)

The way you consume art doesn’t make you a bad person, or a good one. You’ll have to find some other way to accomplish that.

(pp.241-242)

And finally, the final conclusion of the book. I have to say, on a second re-read of this particular chapter I feel quite touch by Dederer words. I don’t know what to do with all the monstrous artists I know, and with their work. I also don’t know what to do with some of my close relatives who are also monstrous and who I also… maybe I still love? Somehow? Or at least a part of me does or a version of me who still has powerfully positive core memories about them?

‘When we talk about the problem of the art of monstrous men, we are really talking about a larger problem – the problem of human love. The question “what do we do with the art?” is kind of laboratory or a kind of practice for the real deal, the real question: what is it to love someone awful? The problem is that you still love her. How often this describes our relationships with our families, our spouses, sometimes even our children. It’s the problem and it¡s the solution, this durable nature of love, the way it whist ands all the shit we throw at it, the bad behavior, the disappointments, the tantrums, the betrayals.

What do we do about the terrible people in our lives? Mostly we keep loving them.

Families are hard because there are monsters (and angels, and everything in between) that are foisted upon us. They’re unchosen monsters. How random it all seems, when you really consider it. And yet somehow we mostly end up loving our families anyways.

When I was young, I believed in the perfectibility of humans. I believed that the people I loved should be perfect and I should be perfect too. That’s not quite how love works.’

(pp. 255-256)