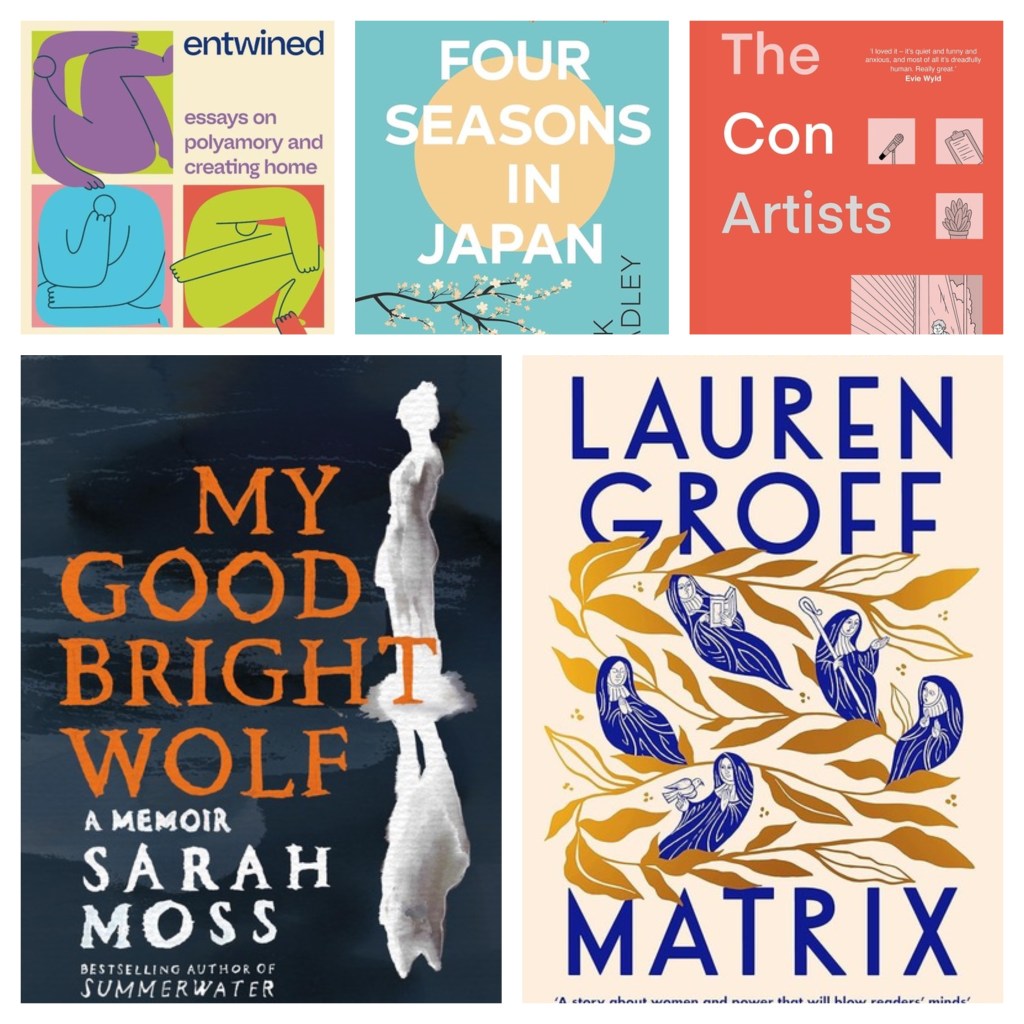

The Con Artists by Luke Healy

I loved How to Survive in the North and Americana by the same author. I found this one in the library and immediately picked it up. This is an interesting story in that it’s framed in such a way that you are never sure if it’s autobiographical (like Americana) or a complete work of fiction (like How to Survive in the North).

This is the story of Frank and Giorgio, two gay men living in London. Their friendship goes way back: they grew up in Ireland and their families know each other. But as adults, they’ve also grown apart and even though they live in the same city, they rarely see each other. Frank is far too busy, focusing on his goal of becoming a reputable comedian and struggling with an anxiety disorder. However, when Giorgio gets hit by a bus and ends up hospitalised, it’s Frank he callsin the first instance. Horrified seeing Giorgio doesn’t have anyone else (and that he refuses to tell his family what happened not to worry them) Frank agrees to move in temporarily with his friend as he recovers from his wounds and needs a bit of help to get around the house.

As soon as they start living together, Frank starts noticing a few strange things. Giorgio is unemployed and living on benefits, yet there are a few luxurious items lying around the house. On top of everything, Giorgio spends his day buying extremely expensive designer products online, such as bags and clothing. Where is all that money coming from?

Don’t get fooled by Healy’s simple (yet emotive) style. This is a complex character study. A depiction of a flawed friendship. A reflection on how, as life goes on, those around us who we may have known very well can change in ways we could have never predicted.

I enjoyed this quite a lot and related to Frank’s struggles with anxiety and panic disorder as he tries to make it as a comedian.

My Good Bright Wolf by Sarah Moss

I loved Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss – gothic, strange, a meditation on Brexit, the dark side of nationalism and celebrating‘that wonderful past in which the invaders weren’t here and everything was perfect’. Then I read Summerwater which I also thought was very good. When I read in the news that Moss had published a new book – and a memoir, no less – I got my hands on a copy as soon as I was able to, even though I didn’t expect it to be an easy read given the main focus (her struggles with anorexia).

Well, it didn’t disappoint. The reading experience was indeed disturbing because I related to some of the experiences as someone who has also struggled with disordered eating and feeling an intense hatred of one’s body for not being ‘right’ or, let’s be frank, ‘thin enough’.

This memoir covers Moss’s life from even before she was born – giving us a short overview of her family, who comes from England and Scotland but also the north and east of Europe via the United States – to pretty much the present day, focusing on the development of her disorder eating.

It experiments with different things. Moss’s early life is told in a fairytale tone, with her parents given epithets such as‘The Owl’ and ‘The Jumbly Girl’ whereas her younger brother is referred to as ‘The Angel Boy’. These childhood sections were especially hard to read as you realise that Moss’s family see ‘fatness’ as a moral failure (which is interesting, considering that Moss’s mother is a brilliant woman with a PhD but also constantly being bullied by her husband for not being able to adhere to her diets and lose weight). As early as four, Moss receives the message from her parents that she’s ‘fat’ and should be careful with what she eats. When years later she has the flu and loses a lot of weight, she receives compliments because of her self-control. It’s easy to see that these were all the ingredients for a child to develop an eating disorder and later on, anorexia, even though it’s clear that it was never the parents’ goal.

Moss is very frank here about her obsession with restricting what she eats and losing weight, whilst, at the same, time, she doesn’t find herself constricted by other artificial ways of performing her female gender – which shouldn’t surprise us,since she’s an outspoken feminist. For instance, she confesses she’s never had an interest in make-up, fashion, shaving, or presenting herself as ‘beautiful’. Yet she’s always had to control her weight and keep it under an acceptable ‘minimum’ to feel like a worthy human being.

Her description of going through a life-threatening crisis during the Covid pandemic was equally chilling. One would think that at that point – when she’s already a brilliant writer and academic, having received acolytes and prizes, when she’s also a mother and married happily, and lives in Ireland after deciding she doesn’t want to live in England anymore after Brexit – you’d think that she’s above the illness that has followed her for so many years. But no. She falls into the‘health’ trap – she starts listening to what she calls ‘experts’ in podcasts as she runs mile after mile in the Irish countryside. These experts invite her to fast for longer periods each time and convince her she can be perfective capable of enjoying gruelling exercise without feeding her body enough energy. They promise her that not eating will make her smarter, and will allow her to think even more clearly, which is obviously not the case. One of the saddest things in the memoir is her realisation that as she starves her body to the point she’s near death she’s lost the ability to write fiction. Shecan’t create anymore.

Her stay in the hospital during the pandemic – without barely any resources, without her family – and how close she comes to being sanctioned – to losing every freedom and privilege because she’s not considered of sound mind refusingas she does to eat even though her organs are already failing her because of it – really made me think of the healthcare system and how we take care of people with mental health illness. Moss explains that hospitals and mental health facilities are designed in a way that almost everyone working there believes patients not to be reasonable at all in any circumstances.

For example, they don’t allow her to walk outside (sure, she’s extremely weak, but also, anyone restricted to a bed for days would go mad) and they don’t allow her to walk to the lower floor either when she complains that the communal toilet in her floor is too dirty to be used (this was the height of the pandemic, where cleaners were not even coming regularly to hospitals).

She goes as far as to quote a study in which a handful of researchers checked themselves in these mental health facilities to prove the theory that as soon as you get checked in, nothing that you say or do will be considered rational. Once these researchers were done, they explained what they were doing to the staff and requested to be let out. Of course, they weren’t allowed to simply leave, and it was difficult to find legal ways of showing they were really researchers doing an experiment and that they hadn’t gone mad (this seems the plot of a horror film, doesn’t it?)

Another aspect of this memoir is Moss’s examination of some of her female literary heroes and their relationships with food – including characters from Swallows and Amazons, Little Women and Jane Eyre.

Throughout many sections in the book, Moss writes about herself in the second person, addressing some issues with her own narrative, mainly, how her memory of the events may contradict what other people involved remember about them,or how she may be unfair to her parents in some occasions – they were not villains, she constantly reminds us, they gave her a privileged education, they fed her and her brother the best organic food they could afford, they passed down their love of hiking and travelling that she shares with her own children… and so on. It is in these extracts when the figure of the ‘good bright wolf’ appears – a mythical creature, a guide who seems to be there to protect the vulnerable child Moss was once and support her as she revisits some very painful moments. This is somehow unexpected, as the author reveals that, in real life, she’s utterly terrified of dogs. Later on, we get to a scene in which she encounters wolf tracks during a run in the Swiss countryside, and she’s both terrified and elated about coming so close to this beautiful and also dangerous animal.

Like life, this memoir doesn’t have a happy ending. It doesn’t leave us with Moss completely cured of anorexia and feeling able to eat whatever she wants without spiralling down into a life-threatening crisis. But she does tell us that she stopped listening to the ‘experts’. That she started learning about fatphobia and she found comfort in that. That, in any case, not eating didn’t make her a better human, because it actually robbed her of what she loved the most – the ability to create stories.

This was one of those books that moved a lot of things inside me and made me feel queasy. But it was also brilliantly written and it certainly felt like an exorcism the author has performed on herself.

Four Seasons in Japan by Nick Bradley

Bradley is one of those authors whose style I love. Like Murakami, like Sally Rooney, he can write about whatever he wants – and I’ll likely read it. I just get into his stories very fast, and devour them in a matter of days. (Also, have I mentioned that his books always have cat characters and you can really tell they are written by a true cat lover? YES.)

This particular book was different somehow, as it reads almost as a translation, which, in a way, is the whole point of the book, since it’s meant to be a translation written by one of the characters. Let me explain.

This is a book within a book. We start with Flo, an American translator living in Japan (who already appeared in Bradley’s debut, The Cat and the City). As someone who lives immersed in a culture that is not her own, with all the joys and challenges this brings, I was already interested in this character and eager to read more from her.

In Four Seasons in Japan Flo is not doing well – her romantic life is a mess since her partner decided to move to New York and Flo stayed behind in Tokyo. By chance, she finds a book in the underground – from a publisher and an author she’s never heard of. Fascinated by the story, she starts translating it into English even though she doesn’t even have permission to do so. What she translates is the bulk of Bradley’s novel.

Organised by the seasons, this ‘Japanese’ novel follows the story of Ayako and Kyo, a grandmother and her grandson living in Onomichi, a small rural town in the mountains. Ayako has a little café in town and is obsessed with hiking and climbing mountains. Kyo loves drawing but struggles after failing his exams to enter Medicine at university (which is the reason why he had to move in with his grandmother in the first place, to be in a quiet environment, away from Tokyo, where he is from, so he can focus on his studies and retake the exams again).

One of my favourite things about this book is how it explores the idea of failure and what that means to people belonging to different generations. Both Ayako and Kyo see themselves as ‘failures’ for very different reasons. Both have had to deal with unspeakable loss and still found the drive to rebuild their sense of self.

It was also refreshing to read a book with an old woman as one of its main characters. I really liked the character of Ayako – we share a fascination with mountains and an obsession with hiking, after all.

Flo’s story I was less convinced by – I started the book thinking she would also have a significant part in it but really her timeline is more like a device to justify the existence of ‘the translated book inside the book’.

When I was listening to an interview with Bradley he mentioned how he had written a second novel that read more like a translation than a novel per se. I think I understand what he means by that, considering his choice of writing about Japanese characters in Japan. As an immigrant, I relate to the desire to write about where you live even if you haven’tbeen born there (or writing about a place where you spent a significant portion of your life). Right now, the stories that come to my mind are often set on this island where I’m currently typing from – and not in Spain, a place I left when I was still pretty much a child. Living between two cultures and social contexts brings in a feeling of strangeness and displacement that can be painful but also inspiring when it comes to creating work.

Matrix by Lauren Groff

A friend recommended this book and finally, I found a copy in the library. It’s set in twelfth-century Europe, and itfollows the real-life character Marie de France as she is forced to leave Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine’s court and sent to an abbey in the bleak English countryside.

My friend was right: I loved this book. I was very much inspired by Groff’s approach to the historical fiction genre, very similar to Kirsty Logan’s in her novel And Now She Is Witch which I read last year. These books are not necessarily focused on plot or on showing a wide depiction of society at the time but rather they seem more interested in character, voice and feeling. And by doing that, they truly transport you to a time that feels as unfamiliar as uniquely thrilling.

This novel, which is also a character study, covers Marie’s life from the time she’s seventeen to her death. I loved how she goes against so many preconceptions we could have about the medieval ages. For one, she comes from a family of strong women, and she’s brought up by her mother, grandmother and aunts who teach her how to become self-sufficient before they die (which happens when Marie is still a teenager because back then life was hard and a cold could end you!)

Sent to the abbey, Marie is heartbroken – she’s separated from her lover and servant (who decides to stay in the court,because that’s where all the interesting things happen, of course) and also from Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine – a woman she loves (and now hates) in equal measure.

Things get hard for her: the abbey is a miserable place where the nuns starve and die as they don’t do much apart from praying. They can’t even grow their own food. But Marie is strong and willing to do anything to survive. She decides to put all the talents and skills she learned from her family to good use trains the nuns so they can hunt for food, and she also teaches them to harvest the vast amounts of land they own. In the beginning, there’s a lot of criticism and the other nuns (and the wider religious establishment they are part of, the Catholic Church) question if all that Marie is telling them to do is really God’s work.

But soon the abbey flourishes and by then Marie has been chosen as the abbess. She embraces her role as a leader and turns the abbey into a commune where any woman is welcomed – no matter who she is or where she comes from. It also becomes a place where women can flourish: where they can live well learn valuable skills and enjoy each other’scompany.

I mean, an abbey as a sort of queer feminist commune in the medieval times? Yes please!

Not everything is easy, and as we follow Marie through her adulthood she encounters different challenges. The Catholic Church is not pleased with all the power she’s gaining. Queen Eleanor of Aquitaine, on the other hand, seems quite amused and through time both women develop an epistolary friendship even though Eleanor never takes Marie’s offer of coming to the abbey when she retires to spend her final years there.

As the abbey becomes more prosperous, Marie starts having visions which show her the abbey as a utopia, a powerful country free from laws and rules made by, well, men. Using the riches they have accumulated by taking care of the land and trading the animals they farm and the produce they grow, Marie expands the abbey, beautifies it and even builds a real maze around it so they can be protected from any external threat. (Which of course means that people plot an invasion because the moment you start building up walls everyone starts wondering what it is you have inside that you are protecting…)

All throughout the story, Marie embraces her own queerness openly, taking a few lovers from amongst the nuns. I really enjoyed that aspect of the book – how queerness is celebrated and written about in sweet romantic terms or in vibrant, sensual detail.

One of my favourite scenes was when the nuns get ready to defend their abbey from an invasion from a group of men who want to raid them. It’s a dark scene, violent and visceral, and it had me on the edge of my seat as I rooted for the nuns but I had no idea how things were really going to end.

By the end of the book, when Marie is old and getting weak, I felt truly moved and sad for the character – she felt like an old friend by then.

I know Groff’s style won’t be for everyone – she definitely favours a lyrical, dream-like approach instead of a plot-focused narrative. But I was completely entranced by this novel and it’s definitely stayed with me. One of the best historical novels I’ve got my hands on in a while.

Entwined: Essays on Polyamory and Creating Home by Alex Alberto

Sometimes you read books you love so much that it seems they were written with you as an ideal reader in mind. Well, this was one of those books, and, accordingly, I devoured it in a few days. What can I say, I love me a good collection of creative non-fiction essays about topics I’m interested in written in an engaging style.

Alex Alberto is a non-binary writer who reflects on their queer journey and their experiences as a polyamorous person looking to establish a family on their own terms,

These essays are often sweet, often sad, but always entertaining. I particularly enjoyed Alberto’s exploration of polyamory and how they realised that a hierarchical system (with a primary partner and secondary partners) didn’t really work for them because the secondary partner always felt left out or they didn’t receive the consideration they deserved. Alberto advocates for a more horizontal system – a system in which everyone works on co-existing together the focus is on creating a wide net of meaningful relationships (not necessarily always romantic ones) with your partner’s partner(s).

It’s all down to consideration and communication, isn’t it? I do think that these are important skills we simply don’t use enough in our individualistic society – so it was very interesting to read about how Alberto was trying to get better at this and what effect this had on their life.

One of my favourite essays in this book was their reflections on realising that they are non-binary and how they struggled to communicate this in their native language, Quebecois, which, like Spanish, is very much gendered (so it’s very difficultto talk about oneself in gender-neutral terms). It was very refreshing to hear the experiences of someone who is also bilingual (Alberto currently resides in the States and they have written this collection in English).

Something else I wanted to highlight about this book is the way it’s been published – I assumed this was published by a traditional publishing house since it looked perfectly professional, but it turns out it’s been published by a collective founded by Alberto and another few writers. I thought this was a fascinating publishing model I haven’t seen before and I wanted to share it here.