Diaries of War by Nora Krug

I love Krug’s graphic novel memoir Heimat, which is a fascinating meditation on the value of historical fiction, not only for the descendants of those who have been treated unfairly but also for the descendants of those who perpetrated violent acts or allowed them to happen because they benefited them in some way or another.

It is clear that Krug is interested in the consequences of war and conflict – and how people deal with them. So Diaries of War is a bit of an experiment (and an interesting one at that). Right after Russia attacked Ukraine and a war between these two countries started (an ongoing conflict) she contacted two people she knew from the arts and literary industries. One was a journalist in Ukraine, and the other one was an illustrator in Russia. She proposed them she’d get in touch once a week to ask for updates on their daily lives as the conflict progressed – she’d then illustrate these to create a book that captured perspectives from both sides.

On the one hand, we have the journalist in Ukraine, K., who was born in Russia but in a territory that used to be part of Ukraine – and now holds a Ukrainian passport. She has two young children and takes them to Denmark as refugees as soon as the war starts. She and her husband spend time there with their children but also regularly go back to Ukraine to cover the war, going back and forth between countries. Their family is torn.

Then we have D., who is a Russian artist. He’s disgusted by the news of the war but he doesn’t know what to do to oppose his government. He is understandably scared as he knows those who are found complaining or railing against it are arrested and worse. At some point, he considers moving his whole family to France, a country where he hopes he can get a passport. He travels to France in the hopes of figuring out a plan and also to avoid being drafted. But when he’s there he realises he misses his family, his home and his culture. He’s not sure if he’d ever be able to leave Russia for good.

These two perspectives are very interesting and harrowing to read. You could argue that D. remains too passive, that he should be out in the street demonstrating even if that puts his life on the line. But I believe that there are so many other things to consider. To start with, the decision to go to war is taken by the ones in power who, more often than not, also oppress their own citizens. I know I can talk for Spain – how it was destroyed after the Civil War and then turned into a dictatorship. To say that everyone living in the dictatorship supported Franco or approved of how he was leading the country would be ridiculous. Especially in a time when you could easily be sent to jail or tortured if you were found to oppose his regime.

In the end, what makes this book interesting is how Krug is recording the perspective of two random people who are on both sides of the conflict. K. Is desperate to get the word out, to show the world how unfair and terrible the conflict is, and she believes that other countries will end up intervening to help Ukraine (which is particularly painful to read in 2024). D’s perspective is perhaps the one people will feel close to – we live in these countries with a strong colonial past (the UK, the US, Spain) which have actively started wars with other countries in the past decades – countries which apparently prefer to spend money on weapons to spend it on their own societies (education, health and the such). And yet we have to make sense of this and of ourselves living under the ruling of those with whom we truly disagree. It’s a terror of its own kind.

This is a book you can read quite fast – more of an illustrated book than a graphic novel, really. It’s also hard, and incredibly sad. It makes you feel very close to these two people and their experiences – for example, when K, narrates what it feels like to leave her flat, that she loves, in Kyiv knowing fully well she may never return, knowing fully well it may be bombed and crumble and cease to exist.

Birnam Wood by Eleanor Catton

I haven’t read Catton’s most famous piece, The Luminaries, for which she won the Booker Prize (as the youngest winner at the time, I believe, and one of the few women). I picked this book because I heard it engaged with environmental anxieties and community. (I heard a scholar discuss it in the same talk he introduced us all to the concept of ‘thrutopia’).

Catton’s style is definitely literary – it reminded me a bit of Donna Tart and Zadie Smith, as she follows different characters all connected through the same organisation, Birnam Wood. This is a collective of people who fight to prevent climate change and do so by planting seeds everywhere – especially in illegal places – as a form of protest. The organisation aims to work as an anticapitalist commune in which everyone’s voice should be heard and considered, but itis effectively led by two women, Mira and Shelley.

The story follows different characters (who, in fact, couldn’t be more different from each other) alternating their points of view. We have Mira, who is ready to do anything to keep her beloved organisation and life project going. There’s Shelley, her best friend, who is tired of doing a lot of work for no income (the joys of running an anticapitalist commune) and, secretly, is applying for better-paying jobs. There is also Owen Darvish, Lord Darvish indeed as he received a knighthood from the Queen of England at the beginning of the story. He’s your classic babyboomer – he has a business as a rabbit exterminator (rabbits are considered pests in New Zealand, where this story is set) which has made him very wealthy. Then we have Lady Darvish, Owen’s loving wife, who can’t wait to show off to all their friends (now that she gets to be a ‘Lady’ by default). There’s Tom, Mira’s ex-boyfriend of sorts who went out travelling all over the world hoping to find a story to tell but ended up being accused of cultural appropriation by some readers of his travel blog who were questioning the way he was describing Mexican people. Tom really wants to redeem himself and find a great journalistic tale to tell.And, finally, there’s the main villain, Lemoin, an American billionaire who is keen to purchase Owen Darvish’s land in the remote Korowai mountains to, apparently, build his own luxurious bunker for when the end of the world hits.

All these characters end up being connected by Darvish’s owned land in the Korowai mountains. It turns out that Lemoin doesn’t want to build a bunker there after all but SPOILER mine a super expensive mineral that is going to make him even richer. But to get away with this he needs to keep Darvish and everyone else in the dark (he’s not really into sharing). And it turns out that Birnam Wood provides Lemoin with the best cover possible to do this: he convinces Mira that he wants to finance them just out of the goodness of his heart (and also, to make Darvish mad, considering that the old man refuses to sell him the land). So Lemoin sends them to the Korowai mountains to plant their seeds illegally on Darvish’s land. Mira knows billionaires are the enemies of anticapitalist communes – but she needs some money to keep the organisation going, so she accepts. At the same time, Tom is researching Lemoine (who he doesn’t trust, if only because he worries he may also be trying to seduce Mira, who he’s had a crush on for years) and starts discovering part of his plan.

This book is half satire, half thriller. Characters are generally explored with all their flaws – Mira and Shelley are selfish and devious at times. Tom’s search for the truth also links to his desire to become a famous journalist and tell a riveting story to people. Lord and Lady Darvish are just a wealthy old couple who couldn’t care less about climate change and the future of the planet. And as evil and hateful as Lemoine can be, we also get a bit of his backstory (and the sense that he’s been alone for most of his life).

This was entertaining to read even though at times it felt a tad too melodramatic. I wasn’t expecting the ending – and it did shock me a bit when I came to it. I think what I enjoyed here the most was the social commentary – I don’t think that the message of the book is that anticapitalist organisations are good and billionaires are bad – it felt more nuanced than that.

Creep by Myriam Gurba

I picked this essay collection at random at a bookshop in Brooklyn (yes, I came back from New York mostly with books, I could barely lift my suitcase!) I love reading creative non-fiction and I’m always looking for new authors. I have never heard from Gurba before, but I was curious to read a Latinx author who is also American.

This is a collection of essays which focus on the theme of the ‘creep’ from very different angles but with an emphasis ongender, race and culture. The first essay is really interesting (and dark). It covers the story of William S. Burroughs – how he shot his partner, Joan Vollmer, and killed her, and how that became part of his legend as a writer and artist. Gurba observes this story really closely and starts analysing its social and cultural context. On the one hand, Burroughs came from a very rich family. His wife didn’t. Their friends knew Burroughs was abusive towards Vollmer. The accident happened in Mexico – Gurba’s family is from Mexico – a country which has had a president, Carlos Salinas, who shot his Indigenous maid in the head (and killed her) when he was four years old. It definitely made me wonder about how violence against women is so ingrained in our society – I believe the story would have been very different if Vollmer had shot and killed Burroughs. It made me consider, for example, another artist, Valerie Solanas, who shot Andy Warhol (and didn’t kill him) – she’s gone down in history in a very different way.

This topic – violence against women and how it has been normalised – is common throughout the book. Gurba exercises a great deal amount of empathy, though. For example, one of my favourite chapters was about her grandfather – she writes both lovingly and critically about him. They share artistic aspirations (his grandfather has a great story, he was a classmate of Juan Rulfo, Mexico’s most famous writer, something he’s always reminding everyone about) and he is also a poet. At the same time, this grandfather never treats young Myriam as an equal (she’s a girl, after all) and she grows up witnessing how sexist he is toward all the women around him.

A few chapters contain anecdotes or moments from Gurba’s life as a secondary school teacher which I found fascinating. In one of them, she observes the racism against Mexicans and Latinx people in the States – how Latinx students are treated differently by some of the other teachers, immediately labelled as dirty and problematic. In a hilarious anecdoteGurba goes to talk to another teacher to call her racism out explaining that she is also Latinx and her confused colleague babbles that she had always assumed that Gurba’s family came from India (as if being Indian is somehow superior to being Mexican?)

In another chapter, Gurba writes about how the poisonous chemicals used in the gas chambers during the Second World War were first tested on Mexicans and Latinx people who were trying to cross the border into the United States – and were forced to undergo a ‘cleaning process’ to make sure they weren’t infectious when arriving to the new country.

Other chapters focus on how white female authors have written Latinx characters – how they have always relied on clichés (and Gurba looks at Joan Didion, who of course has written so much about California, the place where they both,Didion and Gurba, were born) or how they write the sort of damaging narratives that justify the wall and the anti immigrant policies (she includes a very angry review of the novel American Dirt by Jennifer Cummings – a review commissioned by a magazine which refused to publish it arguing that Gurba wasn’t famous enough to be so mean to another writer).

With a completely different tone, there’s a very interesting chapter (sweet at times) about Gurba’s queer experiences and her first girlfriend, a white woman from the Midwest who insists on taking her home for the holidays. What ensues is a great cultural shock from both sides (Gurba’s and her girlfriend’s family), with lots of cringe but also tender moments.

The final chapter was definitely the hardest to read – and I read in the afterword that Gurba placed it at the very endconscious of this fact. It goes over Gurba’s experience of emotional and physical abuse at the hands of a male partner – her first serious partner after she gets a divorce from a female partner she’s had for many years. It was chilling to read, the unfolding of something so atrocious. It’s sometimes easy to judge victims of abuse thinking they should have known better, they should have seen the red flags, especially someone like Gurba who had already been the victim of sexual assault in her early twenties and is not a stranger to misogyny. However things are never that easy, and this chapter is a reminder of that – how you can start a new romantic relationship full of hope, how things can slowly but surely turn differently from what you imagined, how when you realise you don’t want to be in this relationship any more it may be too late – at this point, you may be worried about your life (and rightly so) and completely terrified of your abuser who, by the way, already lives with you.

And of course, explaining the abuse to those around you is never easy – this chapter contains a familiar scene in which Gurba goes to issue a complaint against her abusive partner at the school where they both work as teachers and her boss asks her to reconsider. If she logs in a complaint, she will be ruining this man’s life, which doesn’t seem fair, considering he’s an excellent colleague and teacher.

This is a thought-provoking book about how misogyny is ingrained in our culture, about queerness and the Latinx experience. I really enjoyed Gurba’s writing and I would love to read more by her.

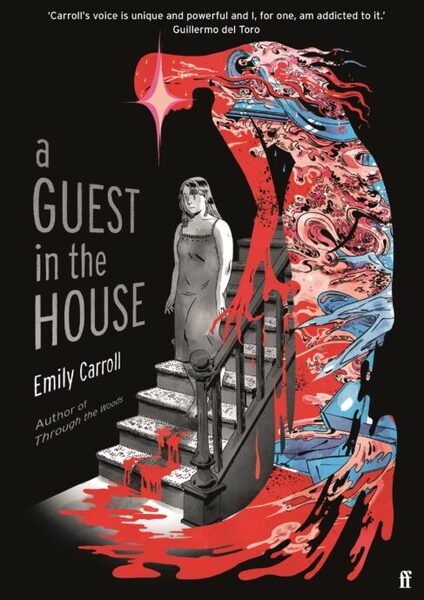

A Guest in the House by Emily Carroll

A lot of similar topics in this graphic novel to Creep – this is also about ingrained misogyny and queerness but narrated in a completely different way. First of all, I’ve been a fan of Carroll’s work since she published Through The Woods, I love her style and her approach to storytelling and surreal body horror.

In this story, we follow Abby, a woman in her early thirties who is married to a dentist. He has a tragic past – his wife died of cancer leaving him and their daughter alone. They move across the country to the town where Abby lives to start a new life – after Abby goes to see the dentist as a patient they start dating and finally marry.

Abby knows she’s lucky – she sees herself as a plain woman with no career aspirations – but she’s having difficulties withfitting into the role of the wife and stepmother to Crystal, her husband’s daughter who is also struggling with grief after losing her own mother. I should also add that this story is set in Canada in the nineties.

From the very beginning, there is a surreal, dream-like quality to the story – Abby likes to fantasise about being a knight in shiny armour who goes to fight a dragon to kill it. The graphic novel is mostly drawn in black and white but Abby’s dreams are painted in lush colours.

I was very intrigued by this book – especially because after a while I didn’t know if some of the things I was reading were really happening or were meant to be all product of Abby’s imagination. I am still not sure after finishing the book but I think this was possibly the point. Although I imagine some people could be left wanting a bit more of a resolution towards the end (I did, but it also prompted me to go back to the beginning, I think this is one of those books which can be read multiple times, getting different interpretations).

There is a bit of Rebecca by Du Maurier in here – Abby wonders about her husband’s first wife – who was a talented artist but also apparently suffered from mental health issues – did she really die of cancer?

There’s also a real level of threat – the idyllic little house where Abby lives with her new family sits right next to a lake which may or not be possessed by a spirit – I particularly had the myth of the Slavic Rusalka in mind, a spirit who takes the shape of a beautiful woman to drag people into the waters.

And then there is Carroll’s gorgeous illustration style – there is so much detail here of the house where Abby feels trapped, of the supermarket where she still works as a cashier, of the woods surrounding the house, the lake, and ofcourse, of her dreams and nightmares.

Mischief Acts by Zoe Gilbert

This is a book with one of the most gorgeous covers I’ve ever seen. And when I read it was about mythology, specifically the figure of the horned god in Britain, I was completely hooked.

Now, this is a very experimental book. A strange one at that too. One of those books which I think it would have been very tricky to publish as a debut or as an author who is not as well-known as Zoe Gilbert. Because this is not an easy read – this demands a lot from the reader, because of the ways it is written, mixing all sorts of points of view and registers and also because you need to work hard, as the reader, to see all the connections that emerge as you go on.

At parts I was a bit confused, I’m not going to lie. Because the chapters are so different from each other I enjoyed some more than others. Sometimes I really connected with a character and then I was sad to move on from that specific context or timeline. Other times there were so many new characters I wasn’t all that interested in them.

Let me explain. This book does engage with the lore, legends and mythology around the figure of the horned god in Britain. Which, I didn’t know, is linked to the legend of the hunter Herne, which is also linked to the legend of the Wild Hunt, which is also linked to the figure of Harlequin. That felt like an amazing discovery, as I was reading the book. Harlequin is inspired by an ancient horned god? (Yes, wonderful!)

The book opens with what I assume is a fictional lecture on the horned god to introduce us to the basics. From then on we follow narratives in which Herne features in one way or another – and as the narratives change into one another he keeps evolving, too. For example, the first one is Herne’s ‘original’ legend, written as a medieval poem. Another one is told from the point of view of a river (this was beautifully lyrical, almost like a prose poem). Another one, Lord of Misrule, is set in the early seventeenth century and is the account of a man, a Puritan, who has the impression that Christmas can be a demonic thing (and as such is written in English from that time). And so on…

The book is also divided into three parts, ‘enchantment’, ‘disenchantment’ and ‘reenchantment’. In the first part, Hern is a powerful and mischievous figure and he is as strong as his surroundings, the Great North Woods (located in what is now London). In the second part, which begins with the eighteenth century, nature starts to disappear and people forget about Herne. In the third part, set in a dystopian future, England has become way too warm and people struggle to survive. They also realise they need trees, and as a necessity they start replanting, and that is how a new version of Herne appears backagain.

I had a few favourite sections (one could consider their short stories, too, which I guess makes sense, because what made Zoe Gilbert famous was her collection of short stories Folk). I loved the one set in the seventeenth century that introduces the legend of the highwaymen and follows a young woman who falls in love with one of them (possibly Herne) who she calls Oberon, to the dismay of her rich (and obnoxious) fiancé. Nullius in Verba, set at the end of the nineteenth century, is the diary of an inventor who is afflicted by a very disturbing disease without knowing it (I won’t say what it is, exactly,because it gives away the main plot twist). The most fascinating thing is that when I researched the disease itself it was, of course, real. I also loved all the sections set in the dystopian future and how Gilbert imagined this future in Britain. As much as it rains here, when it’s warm, it certainly feels like a dystopia. This is not a country for the very high temperatures I’d consider somehow normal in Spain. I was in London in 2022 in forty-degree weather and I also felt like the world was ending. Plus the new legend Gilbert makes up for Herne – as a presence that starts haunting, in a very positive way, the new patch of woods that people have replanted and are trying to preserve – was very interesting.

I’m very intrigued by Gilbert’s work now and I will definitely look into getting Folk next.

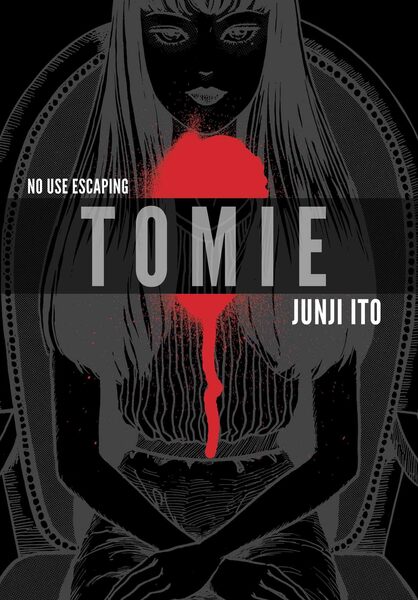

Tomie by Junji Ito

I had never read about Tomie (a very famous character by Ito) before. This collection has many different comics he’s drawn about Tomie. The story follows a teenage girl, very beautiful and sexually precious. Sometimes she’s a bit older (a young woman) depending on the story. She always gets murdered because of her good looks. In the first story (I wonder if this is the first story Ito ever drew of her) she gets killed by her secondary school teacher. She’s been having an affair with him and he gets worried she’ll tell this to someone else, ruining his reputation. So he kills her and makes it look like an accident. Then, when the body is discovered during a school activity in the countryside the teacher and the students plot on how to get rid of the body, as they all feel they could be blamed for Tomie’s death one way or another. Gore ensues as they literally chop the body into small chunks they try to disseminate in the woods. Tomie’s spirit comes back to haunt them.

I suspect the idea of Tomie – the spirit of a young beautiful woman seeking revenge – may be linked to some Japanese folklore. Through the stories that follow Tomie is more of a supernatural being than a girl who is set on destroying the lives of the many men (and occasionally women) she encounters. She first seduces them and then manipulates them to her own advantage. It’s impossible to kill her – she seems to survive even the most terrible wounds. Her body can regenerate at an incredible speed and she’s also able to literally multiply herself like a virus. There’s a lot of body horror here – as Tomie often grows another Tomie from her apparently healthy and beautiful body.

I enjoyed reading this because a character like Tomie in horror is often a character that dies quite quickly and in terrible circumstances. The young, beautiful, sexual woman who must somehow pay for her ‘sins’ by dying a horrible and violent death. I like how Ito subverts this: Tomie can’t be killed, for one. Also, she seems to have a great lot of fun by torturing, killing, and sometimes literally eating those around her. Many people she attacks are themselves monstrous in their actions (like her teacher, for example, who is ready to have an affair with a student and also to kill her to protect his reputation).

Something that got me quite tired though was the repetition. Most of the stories in this large volume follow a very similar pattern – a character gets infatuated by beautiful Tomie, things get complicated when said character discovers Tomie’s true nature, character tries to kill Tomie to be free from her… but they never quite manage.

At some point I was reading this thinking – well, let’s see how Tomie dies in this story (and gets back to life again). But then again, I understand the volume as I read it is a collection of works that Ito has been publishing through the years. This is, apparently, the character which made him famous, and also the character fans keep begging him to draw. So anauthor must.

Will I Ever Have Sex Again? by Sofie Hagen

I read this one by chance, after listening to Hagen’s interview in a podcast. I was intrigued by their experience as a non-binary person and also as a European immigrant in England (pretty much like myself).

I enjoyed this book much more than I had anticipated. In a nutshell, this book explains why its author has decided to not have sex anymore, at least for a while. It’s not because they have realised they are asexual or because they have no interest in sex whatsoever. Rather, it is a conscious decision to examine one area of their life where they always felt uncomfortable.

Hagen is a comedian, and they have a beautiful voice, so if you have the chance to listen to the audio version of this book (as I did) I definitely recommend it. They are a very engaging narrator as they cover the idea of sex (and what sex has meant to them) from different angles.

The book starts with Hagen’s first experiences with heteronormative sex. Being brought up as a woman, they assume sex with a boy is something they are meant to want. They go through with it. It’s alright, not necessarily mind-blowing. But from then on they start having sex with men just because they feel they have to. They do it to show love, to seek acceptance, but their own pleasure is never at the forefront – why should there be? As this book explains, a lot of the ideas about sex are very much male-focused – even the way we think about it (i.e. ‘real sex’ equals ‘penetrative sex’). Everything we watch, we read, even the porn we consume is based on this single fact. But of course, it’s never that easy or simple, especially for those of us who don’t identify as men.

This book also goes over Hagen’s love life – especially one relationship in which their partner was emotionally abusive and manipulative towards them. This relationship is difficult to classify, the abuse was subtle, and in the small details, and it actually took time for Hagen to see it like that. But after realising they’d given years of their life to a person who never cared about them in a meaningful way, Hagen had a breakdown and decided that instead of simply having relationships with men because they felt it was their duty as a ‘woman’ they wanted to stop and reexamine their life.

What follows is indeed a close examination of gender and sex. Hagen realised they were non-binary already in their thirties. Their description of their mother – as someone with more masculine than female traits, Hagen suspects their mother may have been identified as trans if they had been born a few decades later – was especially touching.