The Hollow Places by T Kingfisher

This is the third book I read by T Kingfisher and it’s possibly the one that I’ve found the spookiest. By now I know Kingfisher is an author I enjoy – I’ve literally devoured all her books. What I love the most is her fast-paced writing style and her characters.

In this story, we follow Kara, a thirty-something-year-old recently divorced who goes back to live with her uncle Earl in North Carolina. Now, Uncle Earl has quite a special job. He’s the owner and curator of a very particular museum: Natural Wonders, Curiosity and Taxidermy. You can imagine the deal: all sorts of quirky stuffed animals (including a Fiji siren) and strange artefacts. Kara, however, is anything but spooked. In fact, she has very good memories of growing up around the museum, so when her uncle offers her a job there helping him out she immediately accepts.

Things are going normal until one day, when she’s taking care of the museum while his uncle is in the hospital healingfrom back surgery, she discovers a strange hole in the wall. At the beginning she tries to patch it up but ends up realising that the hole is actually quite large – she gets inside (of course!) and discovers that she’s actually in a tunnel in a completely different dimension. That’s how she ends up accessing another world. Now, this new space she discovers is one of my favourite parts of the book. A strange alien, empty land filled only with water and willows.

I really enjoyed the subtle horror in this book – I imagine is not for everyone but it really worked for me. The empty landscape, the looming threat, the small but terrifying details which kept coming up. It definitely made me feel queasy at points.

I also connected with the main characters. We have Kara, who is lost and depressed after her divorce and doesn’t quite know what to do with her life. And with Simon: her friend and sidekick, a barista from the coffee next door have an excellent dynamic. And of course, there is Beau, the museum’s cat. Kingfisher is an animal lover, you can tell, because she writes animals very well (and she has the humanity and decency of not killing them even though she’s writing horror and the dog/cat always dies in horror movies…)

I also appreciated the combination of horror and alternative realities (which even took a hilarious turn when SPOILER Kara and Simon discover objects from a world which is very similar to ours but not quite like ours… a world in which their Bible has different books written by different apostles and a different horoscope system too…) with mundane worries – Kara doesn’t know what to do with her life and she’s heartbroken not only about the divorce but about realising she actually didn’t love her partner as much as she thought she did.

All of This by Rebecca Woolf

This memoir was well-written and I read it very fast. It was an interesting book to read right after the cosmic horror of Kingfisher because this is about another kind of existential horror, in this case, death, with all its complications.

The premise of the book (and the reason why I picked it up) is quite interesting and powerful. A woman who feels trapped in her marriage because she doesn’t love her husband – in fact, their relationship is so difficult she actively hates him and wants nothing but to get a divorce, something she’s spent years reluctantly avoiding because they have four children together. When she’s ready to leave, the unthinkable happens: her husband is diagnosed with terminal cancer. Surprising herself, she decides to stay and take care of him, even though she’s only doing it because she knows this is a temporary situation.

This book was honest in that it really went on the nuances of hating someone (because you don’t like this person anymore, because this person has hurt you, and done bad things to you) but also being sad that they are suffering, and still being happy once they are dead because they are gone from your life forever. This book was also a critique against marriage – marriage understood as an institution in which women can feel trapped when it forces them to adopt a position of servitude and complacency no matter at what cost. Woolf recognises she married very young, and the reason for this marriage was that she’d got pregnant – she didn’t know what she was signing for, really, and she admits she had a very problematic understanding of marriage and heterosexual partnering. She admits thinking that it was her role to look after her husband (this is, almost immediately turning into his carer by default). She was also very ambiguous about the idea of having sex with him even when she didn’t want to (as in, she was quite happy giving away control over her body). It’s not until many years and three daughters later that she starts becoming more aware of what assault actually is and realises that is not fair (or healthy) to believe that is good to please a man by having sex with him even though you may not want to, even though you may have said no several times but he has kept insisting.

This is also a book about death, of course. She describes caring for her dying husband in great detail. She’s in a very complicated position there as she’s also taking care of their children (their oldest is barely a teenager) who are also going through a lot of grief and conflictive feelings. (Woolf is clear here that her children love their father but they also have a difficult relationship with him because of his anger bursts and mood swings).

Once her husband is dead, then Woolf has to start thinking about family in new ways. On the one hand, she has now a lot more pressure as the sole parent of their four children. On the other hand, she’s exhilarated, feeling free and happy for the first time in years. What follows is an interesting journey where Woolf starts experimenting with dating and having different kinds of relationships. She wants to honour her own exploration of desire and also, understandably, she doesn’twant to end up trapped in a similar kind of relationship to her marriage. She explores her own nescient queerness and consciously practices non-monogamy, a practice that she defends as something that feels more natural for her, at least at this particular stage of her life.

I enjoyed the honesty with which this book was written and how it debunked so many myths about relationships, partnership, marriage and even gender. What came through the book was Woolf’s intense love and adoration for her children. And also, how, in a way, this whole process was a rebirth for her in which she started embodying more of who she really felt like and not who she thought she had to be (the perfect, smiling, complacent wife).

Every time I read a memoir, I’m so in awe of authors who write so honestly about life. It’s comforting to read about women writing about themselves and trying out other roles or paths that deviate from the norm. Also, if you enjoy Rebecca Woolf’s work, or you are curious about it, she has a great newsletter, The Braid.

Sorrow and Bliss by Meg Mason

This was such a baffling book for me – I’m not sure why. I did enjoy reading it and went through it in a few days. It’snarrated from the perspective of Martha, a woman who has just turned forty and lives in Oxford with her husband, Patrick. Martha’s life is in disarray, though, as it is at that moment when her husband decides he can’t be in a relationship with her anymore and leaves. This doesn’t come as unexpected news to Martha: she’s been struggling with her mental health all through her marriage to the point where it’s put a big strain on it. Alone in her flat, wondering if she even wants to save her marriage, Martha ponders about her life to that moment. The book is narrated as a series of fragments covering Martha’s life. Her issues with her own mother, who may or may not have borderline personality disorder. Her love for her younger sister, Ingrid, to whom she’s very close. And, also, the traumatic night when she was seventeen years old and started suffering from an affliction she couldn’t even describe. It didn’t help that her parents were terrified to talk about mental illness so they just downplayed or right-down ignored Martha’s symptoms (at some point Martha explains how she was feeling so unwell she just hid under her desk in her bedroom for days… her parents didn’t freak out… her mother simply started leaving dinner at the door of her bedroom… I mean… what?)

Martha’s adult life is then forever influenced by this ‘illness’ (she doesn’t have any formal diagnosis, but she suffers from long periods of inexplicable grief and despair). Consequently, she struggles with forming relationships with those around her and even keeping a job.

Let’s say it from the very beginning: there were a few things here that I found difficult to relate to. Martha comes from an upper-class family. Her mother and father are not very wealthy themselves because they decided to pursue artistic careers with more or less success – but her mother’s family is rich upperclass so her mother got a flat given to her so she could stay there with her husband and her daughters. So Martha, who of course gets along very well with her rich relatives, is never in trouble when it comes to the financial side of life. This continues when she marries Patrick, a (wealthy) doctor who is very happy to support her both emotionally and financially. As someone who struggles with mental health but never had the luxury to actually stop working (because life, and also because treatment for mental health issues is incredibly expensive and underfunded) I just couldn’t relate and felt a bit exasperated with her family who was so, so emotionally unavailable in every possible scenario (I mean, your seventeen-year-old daughter spends days under her desk in her room out of nowhere and you pretend everything is fine and dandy?)

Although (and my rant is over) I can also see that perhaps that’s the point of the book – to show the life of a woman who apparently has it all (she is beautiful, she comes from a wealthy family, she can afford not to work if she wants to, she has a loving partner – and still she struggles with an unnamable suffering those closest to her have a difficulty to even acknowledging).

There was a character I adored from the beginning, though, and that was her younger sister, Ingrid, one of the few members of the family who tries to address Martha’s issues openly and honestly. The relationship between the two sisters is very tender, moving and believable.

I didn’t know what to feel about Patrick, Martha’s husband. My impression through the book was that their relationship was a bit problematic – especially because Patrick seemed to have this intense drive to become Martha’s carer (it was almost as if, with him being a doctor and the breadwinner in the family he wanted to keep her in that vulnerable position). That’s why I was so surprised when at the end (SPOILER) Martha goes back to him and the two of them decide to give the relationship another try.

There’s another part of this book that infuriated me although I also recognise it’s kind of genius. In perhaps the most important scene of the whole plot, Martha goes to visit yet another doctor. And this time, instead of being prescribed antidepressants (as always) the doctor takes time to listen to her family history and almost immediately diagnoses her with a new disorder she’s never considered before. Which disorder, you may ask? Well, we don’t know. The ‘condition’ is referred to as ‘__’ in the book. Again, as someone who suffers from a mental health disorder, I felt very relieved when I received a formal diagnosis at nineteen (it made me feel like I wasn’t mad, to start with, that my symptoms had a name and a cause… etc.) But I suppose that a mental health diagnosis can also feel constraining, useless labels. And, indeed, there’s still so much stigma around mental health – and specifically around disorders that have been perceived rather negatively and misunderstood such as schizophrenia.

So, to sum up: this is a well-written book. A book that is doing many interesting and innovative things. A good book. Just,not really to my taste. But that’s fine.

I Came All This Way to Meet You by Jami Attenberg

I read writing memoirs now and again. On Writing by Stephen King used to be one of my favourites ( this is a book thatgets recommended ad nauseam in Creative Writing programmes, probably because Stephen King is such as rich and famous writer that all of us are wondering what to do to get there! Also, as a memoir, is very well written, but that shouldn’t be surprising).

I haven’t read any of Attenberg’s fiction but I have been subscribed to her newsletter for a while now. I read that this book was about her travels around the States through different decades as she tried to make a career in writing. I’m very interested in the experiences of those who are unrooted so I picked this memoir to read.

First things first, I loved it. I really, really liked being in Attenberg’s head as I read these pages and I ended the book feeling very connected to her. She seems like such an interesting human being, and I found her reflections on the writing craft both relatable and also inspiring. For example, at one point in the book she talks about gender, about realising she was a ‘girl’ growing up and an awful experience she had with her mother when she took her to a beauty shop in the mall and she got a full face of make-up (just to look at her reflection horrified and unable to recognise herself). From then on she goes on reflecting on ‘beauty’ and appearance: about choosing to present herself in ways that make her comfortable, not ways that only please others.

The book also covers Attenberg’s writing career: from soulless office jobs to realising writing is the only thing she actually loves, to finishing her first book and publishing it. Attenberg has an interesting trajectory – her first three books didn’t do very well commercially, or at least not as well as her publisher expected, so they ended up dropping her. The unthinkable happened when her fourth book was picked by a different publisher and it ended up being the one that kickstarted her career and got her into the bestseller lists.

But even then, when she reaches that point in which she can live exclusively from her writing, Attenberg shows us that the writing life has as many downs as it has ups. For example, there is the misery of having to travel almost nonstopthrough the States to promote her book – with some events being lovely, and others not so. There’s a whole chapter dedicated to her developing a phobia of flying, which of course is very tricky given she needs to take planes to travel around the States. I read those with interest since planes are not my favourite thing in the world (shall we say) but I love travelling (and need to get them to go and see family, who now lives spread all over).

Other chapters focus on the idea of home. For example, Attenberg spent years trying to afford to live in New York, a city that she loves. But the only way she could manage to pay her tiny apartment’s rent in Williamsburg (before Williamsburg was even cool) was by subletting it for a few months every year. An example of this crisis we are all deep in: we can’tafford to buy (or even live) in the cities where we work or want to work (I know this well, having been born in Madrid, a place I’d love to call home again). Her chapter about the apartment building in Williamsburg – and the relationships she developed with all her neighbours – was very touching. In the end, she made peace with the fact that, if she wanted to ever own a house, it couldn’t be in New York. She ended up choosing New Orleans instead, a place where she immediately felt a connection with the landscape and the people – and where she currently resides.

And then, there is friendship. Attenberg writes a lot about it too, especially female friendship, and with other writers like herself. I found that part very inspiring. In her view, the writing life is not only about cracking up words and one manuscript after the other. The writing life is also about creating community, making connections, establishing relationships with other writers and nurturing those. She writes candidly about her friends, showing how they are some of the most important relationships in her life, and friendship certainly receives a greater focus in her book than romantic love.

Another favourite chapter goes over her time in Italy visiting one of such friends (and this is also where I learned about another creepy Catholic thing, that is, about the preserved body of a toddler’s ‘mummy’ in the Palermo catacombs in Sicily, you can read the story here… apparently Attenberg does have a liking for the dark and twisted like myself!)

All in all, this was a very interesting memoir on the writing craft that definitely spoke to me more than books like Novelist as a Vocation which I read earlier this year.

My Child, the Algorithm by Hannah Silva

I loved this book from beginning to end – again, this was one of those which felt they were written for me with my interests in mind. It is a very particular piece – the author, Hannah Silva, decided to use AI to experiment with her writing and incorporated some AI writing into the book itself (the AI writing is in italics, so you can always know which bits are Silva’s and which bits are from the algorithm).

This is an experimental book – it’s a memoir, but it’s also playful and sometimes irreverent, told in a series of short chapters. The main plot follows Hannah’s experience with motherhood. She defines herself as a ‘seahorse parent’ – because she carried her former spouse’s baby (this means, she was carrying a baby conceived from her partner’s egg and the sperm from a donor). Shortly after she gives birth, she and her partner decide to get a divorce, so Silva finds herself alone having to take care of a little baby (she does share custody of the baby with his other mother, but, effectively, she’salso a single parent).

Silva writes about the challenges of having to take care of the baby during the pandemic (I can’t even imagine). She writes about struggling to make a living from her writing career that she combines with other various jobs includingworking in academia on a series of fixed-term contracts (I’ve been there, I know how terrible this feels) plus freelance writing gigs and even benefits (as other ways she can’t afford to stay in London, the city where she works at). All the new experiences (parenthood, the pandemic, having to navigate the dating scene as a single parent and so on) launch Silva into an existential crisis of sorts (I mean, how could it not??) This is when she starts experimenting with the algorithm, asking it questions, offering it portions of her life (situations, pieces of dialogue) for the algorithm to use to create text (and effectively learn).

There’s a very interesting connection here between her child and the algorithm – they are both new things, still a bitunknown to her in many senses. They are also both avid learners and they use language in all sorts of interesting ways as they adapt to it.

I found it very inspiring how this book proposes, by the mere story that is telling, a different kind of family, a different kind of parenting and even a different way of seeing oneself as a parent. Silva may not have a partner who is also a co-parent for most of this book but she writes extensively about the constellation of relationships around her and her child: friends, relatives and even her ex. This book doesn’t sugarcoat motherhood – all the joys and miseries are there – and this is, precisely, what I found most very comforting.

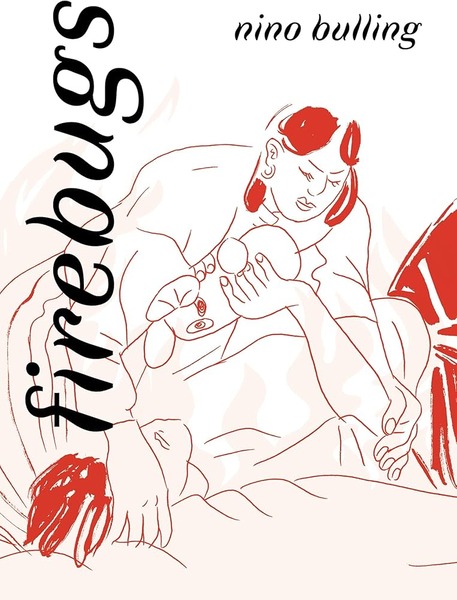

Firebugs by Nino Bulling

A graphic novel I grabbed by pure chance when I visited Forbidden Planet in New York (by the way, for some reason I did struggle to find a proper indie comic book shop in the city while I was there, I’d love to know where the really goodones are!)

I was immediately drawn to the style of the pictures, which is quite distinctive, and the fact that the artist uses black and white illustrations along with the colour red. The book is titled ‘Firebugs’ and I didn’t know what firebugs were (I’venever really seen them in Spain, or in England). So I googled them, and I was like, oh, right, they are a kind of pretty moth. And from then on all I could see in New York were firebugs – everywhere. Especially when I went running in the morning, in the streets of Queens, there would be crowds of firebugs chilling on the pavement. As if there was a convention of firebugs. Well, it was probably mating season…

Back to the graphic novel. This is character-centred work. We follow Ingken, who is just thirty years old, through the seasons, starting with spring. The story opens with a big party where Ingken is trying to enjoy themselves but they are struggling. A lot is going on in their mind: on the one hand, the world is literally in flames in Australia. There are also some worries about the relationship they have with their partner. But above all, this is a book about Ingken trying to come to terms with the fact they are non-binary and what that means for their life going forward. I found it very interesting and nuanced: how the book explores that dread that comes with gender dysphoria but how difficult it actually is to put it in words when you don’t want to become a ‘man’ or a ‘woman’ but something in between.

Ingken’s relationship with her trans girlfriend, Lily, is also explored in the book – Ingken is changing as a person and as a result things are deteriorating between them. Lily is supportive of Ingken’s gender exploration but at the same time, she’sfrustrated by the slowness of it and by the fact that Ingken can’t quite decide what they want yet.

The whole tone of the story is quite melancholic as the characters move through the seasons and their relationships change and sometimes become undone. I was left wanting more when the end came but then again, that’s life – there are no simple answers or resolutions, just a continuum that is always evolving.

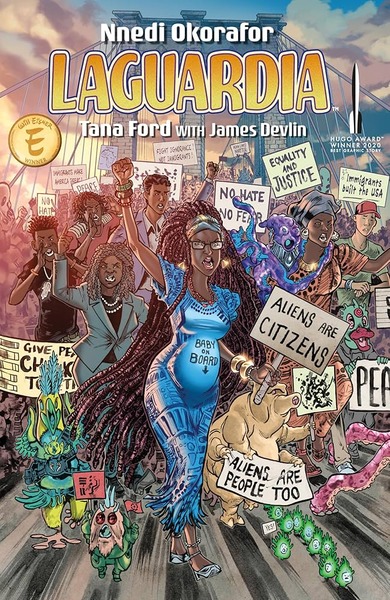

LaGuardia by Nnedi Okorafor and Tana Ford

A friend I visited in Plymouth last August recommended lots of amazing graphic novels, including this one. I was looking for a physical copy of it because I thought the art was pretty incredible and I finally found it in Forbidden Planet in New York (this was the book I originally went for before I started grabbing other random things!)

I loved the premise of this book – the Earth is now home to all sorts of alien creatures – and the place where they first made contact with humans happened to be Nigeria. In the beginning, humans and aliens managed to live together, but through the years there have been more and more tensions as humans start demanding new laws and regulations to control how aliens get to enter the Earth (if they are allowed at all). Other social movements ask for aliens to leave as they see them as a threat to their communities and people believe their influence will end with important elements of human culture.

Of course, this is all very resonant of the world we live in today – where the movement of people (migrants, refugees) is seen mainly as a threat. So many times I’ve talked with colleagues and people I know and I’ve heard the usual ‘but they come and they don’t uphold our culture/values’. There are so many concerns and fears about letting ‘others’ in.

This story follows a Nigerian doctor, Future Nwafor Chukwuebuka, who decides to leave Nigeria pregnant and carrying with her an alien refugee who she successfully manages to smuggle through the US border.

Some of the best scenes in the graphic novel happen at the beginning: for example, when Future has arrived at LaGuardia airport and she’s trying to cross the security control but, of course, she’s stopped. Agents are concerned with her big hair (they think she may be trying to hide things in there) and spend a long time prodding at it (completely oblivious to the fact that she’s carrying the illegal alien, which looks like a little, sentient plant, in her purse).

As Future starts making a new life in New York with her grandmother, a lawyer who lives in the Bronx, the mystery of why she decided to leave her country (and her partner) starts to unravel. In New York there are similar tensions to Nigeria – some people agree with the aliens coming in, others are scared and want them to return back to the planets they are from. Future is keen on saving Letme, the alien she brought from Nigeria, at any cost. Letme is the last being of its kind after an interspecies war killed the rest of its family.

This is a book which uses science-fiction tropes to reflect on what happens when different cultures and ways of living collide in the same space. There is always change after an event like this (for all the cultures and traditions involved) but,does it always have to be for the worse? Can we ever say that culture is something static that needs to be preserved at all costs in its current form? Are there other (better) possibilities?

At some point in the story, Future realises that she’s starting to develop some small plant traits – her hair, for example, starts turning green, and some small vines start growing from it. By being in contact so closely with Letme her whole DNA has been altered and changed forever. She worries about what that may mean for her and her unborn child, but of course, it is too late to do anything about it. In another kind of story, this could be the start of a horror plot (in which a pregnant woman morphs into a plant?). But what makes Okorafor’s work really original is that quite the opposite ends up happening – Future changes, her baby is a bit different from other babies, but this opens all sorts of new and exciting possibilities for their characters instead of making them monstrous.

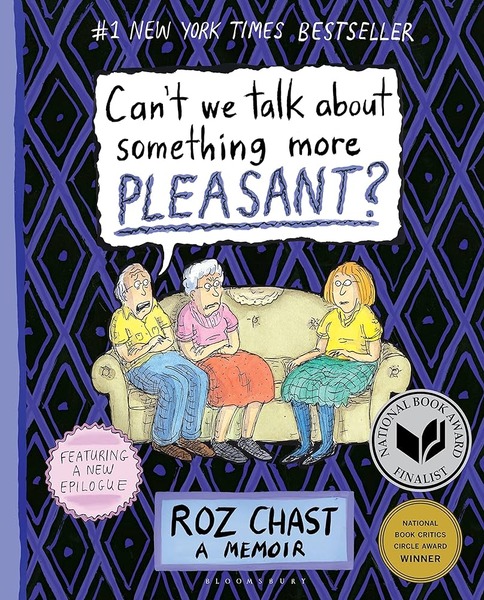

Can We Talk About Something More Pleasant? By Roz Chast

This book hit me quite badly. I picked it up at a bookshop in Brooklyn by chance. I saw it was about a woman taking care of her ageing parents – the process we all should go through as adults if we are lucky enough. I’m normally quite open and ready to read about death, it’s certainly a theme I don’t avoid.

At the beginning, the book – which is a graphic novel, and also a memoir – introduces us to Roz’s quirky family. Her parents had her when they were already ‘old’ so by the time she has young children they are both in their nineties. They live in the same flat where she grew up in Brooklyn, whereas Roz has moved to Connecticut so she can live in the suburbs with her husband, her son and her daughter. Roz’s parents are from a different generation and it’s funny to read all how Roz can’t relate to them. Her father is a hypochondriac who is afraid of everything, even changing a lightbulb. Her mother, on the other hand, is energetic and stubborn and will have a fit of rage every time she gets crossed. Chast is quite honest from the very beginning – she gets along with her father very well but has a more difficult relationship with her mother. She grew terrified of her as a child and as an adult, she just doesn’t like her.

The story continues with Chast visiting her parents and realising that, slowly but surely, things are changing around the house. Her mother is not on top of her cleaning anymore and they both seem to slowly stop coping with the demands of normal life. It’s a tricky situation because her parents have been married for more than sixty years and depend exclusively on each other in a large myriad of ways. They also don’t have friends, and no family is living nearby apart from Chast.

Things only get worse when Chast’s mother has a bad fall that leaves her unable to leave her bed for weeks. She, of course, refuses to go to the hospital. And from then on, things go downhill – with her father quickly developing more dementia symptoms that turn increasingly difficult to ignore.

This is a very grim memoir about seeing people you love and people you feel ambivalent about slowly lose their health and, as a result, their freedom. It got so sad and so resonant of some experiences I’ve had that I couldn’t read this in one go – even though it has some parts that are so funny that they had me laughing out loud (like the wheel of doom, which includes made-up cautionary tales that Roz Chast kept hearing during her childhood, so similar to the ones we all must have heard).

When Chast finally convinces her parents to move into a care home – seeing how they can’t live on their own anymore – she then goes into the flat, that they rent, (which is very common in New York City, I believe), and starts cleaning up and taking photos of all the things she wants to remember. These real photos are reproduced in the book, which makes an interesting break from the illustrations and gives an extra dimension of realism to the book. It was both terrifying and fascinating to see piles and piles of objects which would have made a ‘home’, objects that someone would have looked at as possessions but that in the photos look forlorn, antiquated, occasionally almost like trash.

Chast’s parents’s health declines even faster in the unfamiliar space of the care home. The place where they are is lovely (as lovely as these places can be, I imagine). After visiting several institutions Chast decides to use her parents’ savings to pay for a place that doesn’t feel downright dirty or depressing. Her father dies relatively quickly, leaving her mother alone, and she withers for years. This is an honest memoir – at some point, Chast’s mother is simply lying in bed sleeping and being fed, like a baby. Everyone thinks she’s slowly dying but somehow she just doesn’t, and eventually Chast realises her parents’ savings are going to run out and she won’t be able to afford the care home and the private nurse who takes care of her mother and feeds her and cleans her anymore. I mean, talking about grim.

I finished this book feeling awful and a bit enraged. I felt awful because it seems such a cruel thing that we all work so hard to get a few ‘freedoms’ (to have financial independence and freedom to live as we want to) but we lose all of these in time as we age and revert back to a sort of second childhood in which we need others to survive. At the same time, as a daughter myself, I wonder if I’ll ever be in that position again of having to take care of my elders when so many systems are against us. It’s ridiculous that decent care homes are also so expensive and you can only afford them if you are rich or if your parents were lucky enough to have enough savings. It seems that taking care of our elders is something we should all want to do together as a society.

It also made me think of having a community around you (or not). Chats’s parents don’t really have any friends – in part, one can imagine, because of the very close, co-dependant relationship they have developed with one another. Chast is also on her own since she doesn’t have any siblings or other family members nearby to help her. I wonder if this is something that living in a big city makes to you – or if it’s just simply circumstantial and could happen to all of us. But ideally – and this is one of the things I thought of after reading the book – taking care of your parents as they age and die is a process you wouldn’t want to go through on your own.

Laziness Does Not Exist by Devon Price

This is a very interesting book to read in conjunction with Burnout by Amelia Nagoski and Emily Nagoski (which I reviewed the previous month). I’m someone who has always been interested in productivity and having a writing practice – and suffered from burnout because of it.

Devon Price is an academic, which makes this book especially resonant since he talks about some experiences anyone working at a university would easily relate to. It all starts with Price’s own experience of burnout during his PhD – how he felt pushed to work as hard as he could even when he could barely stay conscious because of the flu. It may seem ridiculous, but academia does that to you. We research the things we deeply care about so, naturally, this work gets intertwined with our identity. Working in academia is not a job in which you clock in and clock out. I had jobs like that before, and some of them were annoying, but the moment I was out of the office or the shop I was free. Academia is different – you are always working, weekends and holidays alike, because you are always considering things that have to do with that research. I try to say to myself that I am, first and foremost a writer and an artist and that my academic job is something I do on the side to make ends meet. But still, it’s difficult.

Then, academia is always so precarious – you are constantly dependent on funding, that you may get, or not, and of publishers and editors who may choose (or not) to publish your work. (I say choose because when it comes to the arts atleast, there is a key subjective factor). The job market is also cruel – it took me six years of non-stop effort that very nearly broke me to land a permanent full-time job (AKA a job I could actually rely on to pay my bills) and still, it doesn’tfeel safe or secure.

So. Laziness. A symptom of my burnout was that I stopped enjoying that which I loved the most, which is, writing. And hanging out with people. And reading. And generally living. It was a strange illness that Price describes in vivid detail. For him, overcoming burnout meant accepting he didn’t want to become a tenured professor (the equivalent of a permanent job in academia in the States) and instead preferred to keep doing part-time jobs at the university so he would have time to write and do other things which I assume supplemented his income and also brought him joy.

If there’s a thesis in this book is that we have been made to believe that being human means being productive – and that without producing we are nothing. Price links this damaging value to the Puritans and their obsession with discipline and work. I still find it relevant even if I don’t have a Puritan background culturally speaking – in Catholicism there’s also this idea that all the good things will come to us in the afterlife, so it’s not a strange thing to be suffering right now. Price also talks about society’s disdain for the homeless and those who don’t seem to be as ‘productive’ as they should, and how ridiculous that is. We should all have inherent value as human beings, and we can’t all ‘contribute’ in the same fixed way. That would be madness.

Price goes on to show, supported by numerous research, that our brains can only do focused work for a few hours every day. Beyond that, what we call procrastination is a safety mechanism to, quite literally, prevent madness. Our brains ‘switch off’ because they are overwhelmed. They can’t be on all the time.

From there, the book goes over different areas in someone’s life – from relationships to romantic partnerships to family, friendships, hobbies and the like – explaining how the concept of ‘laziness’ in every single one of these doesn’t hold. This is a book that contains a bit of Price’s own story but it is majorly informed by interviews Price conducted with lots of different people (as case studies) as well as research that supports his arguments (Price has a doctorate in Psychology, and you can tell).

So this is not a self-help book per se (even if at times it could seem so) but a study against our current views on laziness.We have all been poisoned to believe that we are never productive enough and we literally kill ourselves trying to meet these inhuman demands instead of realising that the system is ridged and unfair and that we should all be fighting for more time and space to live and thrive because this idea of maximum productivity and constant growth is only serving a very few and not the majority of us.

One thought on “Seahorses, aliens and willows: September 2024 Reading Log”