Non-binary Lives, edited by Jos Twist, Ben Vincent, Meg-John Baker and Kat Gupta

(If you notice a theme on my reading for July it is because I raided my library’s showcase of queer books for June…)

This is an edited collection of essays. One of the editors is Meg-John Baker, a British author I keep finding every time I manage to get my hands on books about non-binary experiences. This particular collection has different sections, ‘cultural context’, ‘communities’, ‘the life course’ and ‘bodies, health and wellbeing’. The writers behind these essays are all quite diverse in terms of background, class and race – and their experiences of a non-binary life are very different.

As with any collection, some essays spoke to me more than others. One of my favourites was The Soft Line In-Between written by a German author, Jespa Jacob Smith. They reflect on how gender and language relate to each other, which is something I’m very interested in as a bilingual author myself.

They write in their essay:

‘I grew up speaking German. I love this language. It has lyrical depth at unexpected moments, it is versatile yet so concise. At the same time this language requires so much effort to bend it, to make it flexible enough to find cracks and nooks to get through or hide in. Its harsh, bureaucratic vocabulary, its unwillingness to play around, to even be dismissive of playing around, its emotional flatness and cold “stick to the rules” manner oftentimes render you at a loss for self-expression.

My way of speaking has always been called “peculiar”. Even before studying philosophy had given me a thousand new ways of expressing myself, I had been told that I have an “interesting way of saying things”. In a way this statement felt at least like some recognition of how I see the world. Language presented me with the tools to change things right away, to bring awareness to details, to the unseen, to the little glitches reality offers that usually languages try to rope in and control. I wanted to express these glitches as I felt somehow I was creating one myself. But when I was younger I couldn’t yet express how. In German it is difficult to be gender “neutral”. It requires a level of skill that even native speakers do not usually have, the use of a lot of passives and workarounds. We are not trained to speak that way. (…)

I very distinctively remember that moment when – I was about 16 – I realised that I could talk about myself and did not have to use a gender specific word. That it could just be me and the things I did, I liked, I wanted. I discovered the subtlety of the use of “they” when talking about a person of unknown gender. What I didn’t know at the time was that there were actually people who used this pronoun for themselves.’ (p. 40)

Genderation, another essay, this time by Lucy/Luc Nicholas also spoke to me – Nicholas also works in academia and alludes to gender theories on feminism and transness. They also write about how, because they were mostly presenting as femme, (and most people would read them as a woman), they didn’t feel they ‘deserved’ making a fuss to come out as non-binary. This sounds so familiar, this people-pleaser attitude, this ‘don’t rock the boat’ those of us who have been educated as women are hammered with from so many fronts (family, school, the media…) In the end, Nicholas defends their right to identify as both, as a feminist and as a non-binary person:

‘Finally, then, it may sound silly that as a gender scholar I had never thought of this, but last year two of my good queer academic friends told me they felt it is more radical to be a woman and present non-traditionally than to identify as non-binary or genderqueer. And I was stumped. Am I betraying other women, taking the “easy” route, by challenging the existence of the category rather than transforming it?

Being a butch woman does seem to challenge and upset people more than being a masculine non-binary person. So it is inherently more subversive? I think one of the issues is the perception that all the masc presenting people are “going” non-binary. In my observations this is occurring to some extent, but I know just as many non-binary folx who are femme or fluid presenting. Like me! In which case, all the categories get expanded. Woman isn’t being abandoned. (…)

I’m feminist and non-binary. I’ll go on the Women’s March and Trans Pride. I’ll go to the lesbian bar. ‘Cause there is the world that is and the world that I want. The identities I am given and the ones that I make. I can relate to feminism, not just because the identity of woman has been imposed on me all my life and therefore shaped my existence and opportunities, often in a restrictive way, but because gender does this, full stop. I don’t have to be an essentialist to strategically invoke woman or lesbian when needed. Many of my younger friends and the communities they hang out in have no problem being both non-binary and feminist.

Until we can get to a utopian place where sex/gender markers lose their sexed/gendered meanings and anyone can present as they want to present without worrying too much about the identity attached to it, I am going with more choice, not less.’ (p. 172-73).

Funny fact: through this book, I also learned that some people choose to spell the word ‘human’ as ‘humyn’ – apparently to take the word ‘man’ out of it. Uh!

All in all, this is an interesting collection of essays by non-binary writers. I enjoyed it way more than anticipated and, if anything, I just wish some of my favourite essays here would have been longer.

Greedy: notes from a bisexual who wants too much by Jen Winston

This was a memoir written about the author’s experience with bisexuality – with this term understood as an attraction to different genders, not just the female/male binary. This was a quick read for me, and even though there were things I enjoyed, it wasn’t all that memorable. I think there was something about the style that didn’t quite click with me. It was obvious that Winston was trying to push some boundaries with this book, with many of its chapters trying on some experimental formats (one chapter is written as a film script, for example, another one as an email exchange… and so on). Even so, the style overall was simple and it reminded me of the informal, easy-going tone employed to write blogs or web content. I suppose I’m a bit spoiled after read other non-fiction books (by Leslie Jameson, Erin Riley, Olivia Laing) where you can tell the author is extremely accomplished at using language and form.

Also: for a lot of it I didn’t relate to the experience the author has of bisexuality – half of the book was about her experience dating boys from her teenage years until she’s in her thirties. She spends most of this time seemingly accommodating to the standards of female heteronormativity and not questioning them much. At times she’s trying so hard with some awful partners that you almost want to come in there and ask her to get herself out of a tricky situation. Although, of course, always easier to see these things from the outside.

Something this book does quite well, though, is exploring the nuance of the word ‘bisexual’, and how it can be expansive and include different genders. It also criticises the fact that many times this same label is treated as something that doesn’t exist, questioned by people outside and inside the queer community. Winston’s experience of friendship and polyamory was also of interest to me – and to a point I wish she had expanded more on this, on the idea of how bisexuality challenges the structures of a traditional family.

Testo Yonqui by Paul B. Preciado

I loved Disphoria Mundi by the same author, which I read in January of this year. Testo Yonqui is a much earlier work, published in 2008, when Preciado was in his thirties and living primarily in Paris. I found this book so fascinating and pretty much like the previous one I devoured it in a few days. Preciado, to me, is the Spanish Maggie Nelson, which anever heavier dosage of philosophy (which shouldn’t be surprising, he’s, amongst other things, a philosopher). I’m so in love with his job, with the audacity of it, with the way it never fails to challenge me and shock me.

This book is written in chapters which alternate in terms of tone – some of them are autobiographical, and others are heavier in terms of theory and philosophical reflections. The autobiographical chapters in this book are written in a raw, lyrical style and follow the journey of Preciado (who back then still identified as a woman) experimenting, for the first time in his life, with small doses of testosterone (he’s applying these to himself in the form of a gel on the skin). One could say that this book’s thesis is to propose that each individual is entitled to the freedom to alter their hormones if they wish to. After all, Preciado reminds us, this is what women have been doing for decades by consuming different hormonal birth controls (which have lots of side effects, including cancer, but which can be, nonetheless, very desirable for obvious reasons). This is a very interesting argument – I grew up in a society in which parents saw no issue in giving the pill to their thirteen-year-old. I’ve also seen first hand. Now, those same parents happy to hand away the pill may be very well against letting that same thirteen-year-old daughter use testosterone in the form of a gel at that time or much later in life.

Preciado writes:

‘Nuestras sociedades contemporáneas son enormes laboratorios sexopolíticos en los que se producen los géneros. El cuerpo, los cuerpos de todos y cada uno de nosotros, son los preciosos enclaves en los que se libran complejas transacciones de poder… cuyo objectivo es la producción, la reproducción y expansión colonial de la vida heterosexual humana sobre el planeta.’ (p. 94)

‘Our contemporary societies are large sexopolitical labs in which the genders get produced. The body, the bodies of each and every one of us, are the precious enclaves in which complex power transactions take place… the aim of those is production, reproduction and colonial expansion of human heterosexual life all over the planet.’ (p.94, my translation).

He’s also a multilingual author and someone who has lived in Spain, the States and France – I believe he currently calls Paris his home:

‘Entre tanto, disfruto de lo que tengo. El placer único de escribir en inglés, en francés, en español, de caminar de una lengua a otra como tránsito de la masculinidad a la feminidad, a la transexualidad. El placer de la multiplicidad. Tres lenguajes artificiales que crecen enmarañados, que luchan por convertirse o no convertirse en una sola lengua. Mezclándose. Encontrando sentido en esa sola mezcla. Producción entre especies. Escribo sobre lo que más me importa en una lengua que no me pertenece (…) Ninguna de las lenguas que hablo me pertenece y, sin embargo, no hay otro modo de hablar, no hay otro modo de amar. Ninguno de los sexos que incorporo posee densidad ontológica y, sin embargo, no hay otro modo de ser cuerpo. Desposesión en el orígen.’ (p. 104)

‘Meanwhile, I enjoy what I have. There’s a unique pleasure in being able to write in English, French and Spanish, in being able to change from one language to the other as I transit from masculinity to femininity to transness. The pleasure of multiplicity. Three artificial languages which grow intertwined and fight each other to become (or not) a single tongue. Mixing up. Finding sense in that single mix. Reproduction amongst different species. I write about what I care about the most in a language which doesn’t belong to me (…) None of the languages I speak belongs to me and yet there’s no other way to speak, to love. None of the sexes I incorporate to this language possess an ontological density and yet there’s no other way of inhabiting a body. Dispossession right at the origin.’ (p. 104, my translation).

There are very interesting chapters here on how gender and witchcraft relate – I’d never seen this argument before but I found them fascinating. There’s something in witchcraft and magic which is very much about regaining control and having the power to make things happen for ourselves, which is something that institutional power (hello, Catholic Church and the Inquisition) have been very much against:

‘La persecución de las brujas a finales de la Edad Media puede entenderse como una guerra de los saberes expertos contra los saberes populares y no profesionalizados, una guerra de los saberes heteropatriarcales contra los saberes narcoticosexuales tradicionalmente ejercidos por las mujeres y los brujos no autorizados. Se trata de exterminar o confiscar una cierta ecología del cuerpo y del alma, un tratamiento alucinógeno del dolor, del placer, de la excitación, y erradicar las formas de subjetivización que se producen a través de la experiencia colectiva y corporal de rituales, procedimientos de transmisión de símbolos y procesos de de asimilación de sustancias alucinógenas y sexualmente activas. La persecución de la brujería que abre la modernidad esconde, bajo las acusaciones de la herejía y la apostasía (renegar de Dios), la criminalización de las prácticas de “intoxicación voluntaria” y de autoexperimentación con sustancias alucinógenas y con la propia sexualidad. Sobre este olvido inducido se asentará la modernidad eléctrica y hormonal.’ (p. 117-118)

‘The prosecution of witches at the end of the Middle Ages can be understood as a war between expert knowledge and popular, unprofessional knowledge. A war between heteropatriarchal knowledge and the narcosexual knowledge traditionally embodied by women and male witches with no authority whatsoever. This is, then, all about exterminating or confiscating a corporeal and spiritual ecology, a hallucinogenic treatment of pain, pleasure and excitement, and eradicating those forms of subjectivity which are produced through the collective and corporeal experience of rituals, procedures of transmission of symbols and procedures of assimilation of substances which are hallucinogenic and actively sexual. The prosecution of witchcraft which kickstarts modernity hides, under accusations of heretics and apostasy (that is, of denying God), the criminalisation of those practices of ‘voluntary intoxication’ and of auto experimentation with hallucinogenics and sexuality. Our current electrical and hormonal modernity is built on top of this oblivion.’ (pp. 117-118, my translation).

The more personal chapters of this book follow Preciado’s romantic relationship and infatuation with his then-partner Virginie Despentes. How, through their relationship, Preciado finds himself as addicted to her as he’s addicted to the microdoses of testosterone he’s taking.

‘… como feminista, parece urgente testar sobre el propio cuerpo los efectos farmacopornopolíticos de las así llamadas hormonas sexuales sintéticas. Precisamente porque he crecido en el feminismo culturista queer americano y me he convencido, con Foucault y Butler, de que la feminidad y la masculinidad son construcciones somáticas, puedo y en algún sentido debo experimentar con esas construcciones. En un mundo donde los laboratorios farmacéuticos y las instituciones médico-legales estatales regulan el uso y el consumo de las moléculas activas de la progesterona, el estrógeno y la testosterona, parece anacrónico hablar de prácticas de representación política sin pasar por experimentos performativos y biotecnológicos de la subjetividad sexual y de género.’ (p. 257)

‘… as a feminist, it seems urgent to test on my own body the pharmacopornpolitical effects of the so-called synthetic sexual hormones. Precisely because I was brought up in this body-building American queer and I have been convinced, by Foucault and Butler, that femininity and masculinity are semantical constructs, I can, and actually, I should,experiment with these constructs. In a world in which the pharmaceutical labs and the medical-legal institutions regulate the use and the consumerism of active molecules of progesterone, oestrogen and testosterone, it seems an anachronism to speak about political practices of representation without going through the performative and biotechnological experiments of the subjectivity found in sex and gender.’ (p. 257, my translation).

‘Pensar este principio autocobaya en relación con las políticas de género y sexuales implica que no es posible darle consejos a nadie sobre si tiene que gestar esto o aquello, sobre si debes o no follar con condón, sobre si este es el porno que te tiene que excitar o no, sobre si la mejor sexualidad es la lesbiana o la SM, sobre si te la como o me lo comes, sobre si es mejor tenerla o no tenerla, sobre si es mejor tomar o no tomar hormonas, sobre si es mejor operarse o no. Frente al parroquianismo y el adoctrinamiento moral que ha dominado las políticas feministas, queer y de prevención del sida, es necesario desarrollar micropolíticas del género, del sexo y de la sexualidad basadas en prácticas de autoexperimentación (más que de representación) intencionales que se definan por su capacidad de rechazar y de resistir a la norma, de crear nuevos planos de acción y de subjetivación.’ (p. 265)

‘If we apply this guinea pig principle to gender and sexual politics this means that it’s not possible anymore to give people advice about what they should gestate or not, or if they should fuck or not with a condom, or if this is the porn that should or not excite them, or if the best sex is lesbian sex or BDSM, or if I suck you or suck me, or if it’s better to have it or not to have it, or if it’s best to take hormones or not take them, have surgery or not to have it. To challenge the moral indoctrination which has dominated feminist and queer politics, as well as those based on AIDS prevention, it’s necessary to create new micropolitics of gender, sex and intentionality based on autoexperimentaton (more than representation) which will be defined by their ability to reject and resist the status quo, and their ability to create new plans of action and subjectivity.’ (p. 265, my translation).

Another interesting part of this book is when Preciado writes about his experience with drag (in this case, drag kings) andhow he attended his first workshops and learned from other drag kings to perform masculinity.

‘Cuando hago un taller con Diane / king Dani, yo soy su chico de los recados, su traductor, su maquillador, el chaval que le recoge las colillas y le limpia los zapatos, y él es el Master. Estoy ahí para aprender del jefe y hacerle sentir al jefe, pura ética king, que es el jefe…. Y ese poder no se declina, porque si lo declinas a favor de otro o de otros, entonces has perdido tu caché king. Esta es una de las primeras lecciones sobre la masculinidad: todo depende de una gestión del poder, de hacerle creer al otro que tiene el poder, aunque en realidad lo tiene porque tú se lo cedes; o bien de hacerle creer al otro que el poder, de forma natural e intransferible, lo tienes tú, y que tú y solamente tú podrás darle al otro el estatuto de masculinidad que necesita para pertenecer a la clase de los dominantes.’ p. 270-271.

‘When I do a workshop with Diane / king Dani, I’m his errands boy, his translator, his make-up artist, the guy who picks up his butts and cleans his shoes, and he is the Master. I’m there to learn from the boss and make him feel boss (this is pure king ethics)… This kind of power can’t be declined, because if you say no to it so someone else can have it, thenyou’ve lost your king caché. This is one of the first lessons I learn about masculinity: it’s all about the management of power, about making the other believe that they have the power, even though they actually have it because you are giving it to them. Or perhaps about making others believe that you are the one who has the power now, in a sort of natural and non-transferable way, and that only you can give them this masculine status they need to belong to the dominant class.’ (p. 270-271, my translation).

A very interesting book that I wish was more well-known in gender studies. There’s an English translation out there (Testo Junkie, translated by Bruce Benderson). Everyone interested in body autonomy, queerness, gender and the trans experience should read this. Preciado is now definitely one of my favourite authors and I can’t wait to read more by him.

Voice of the Fish by Lars Horn

You know when you read something that it seems was written for you and only for you? Well, this book was that for me. I picked it up from the library (again, thank you to the library staff who created that wonderful queer shelf that I raided back in June). I wasn’t sure by the blurb if I’d like it – if the voice was going to be too nebulous, too lyrical, too abstract. But no. The first page of this book already had me hooked because the prose is so beautiful and confident – all testament to the craft of its author.

This is a book composed of different lyrical essays – some experiment with form quite openly, others are more traditional, but all are equally engaging, well-researched and fascinating. A real masterpiece in the lyrical essay form.

Fish, Horn’s obsession, are a recurrent image that ties all the chapters together (including the fascinating story of Jeanne Villepreux-Power, a marine biologist from the 18th century and the first woman to create a modern aquarium). I’ve never learned so much about fish before, but the way Horn portrays them they definitely come across as fascinating creatures. For example, thanks to this book I learned that there is a shark that lives hundreds of years. Yes, you have read correctly. We are talking here about the Greenland shark, who reaches maturity at the tender age of one hundred years old.

At the same time, this is also a book about Horn’s life: about his relationship with art, which started in his childhood partly thanks to his mother, a visual and performing artist who used Horn (as a child, then as an adult) in her pieces – going as far as to photograph him in a bathtub full of dead squid (this is the title and topic of one of the first essays in the book). Horn also describes, with very specific detail, the process of making a cast using his whole body. It sounds terrifying – but also, that he could go through this (for his mother’s artistic purposes) several times during his life speaks of the supreme mental force of the author (I could never…)

Other things are covered here too – Horn’s travels through Europe and the States as a student and then as a writer. His experiences with gender and queerness, realising that he’s a trans man, coming to terms with the homophobia he encounters in many places he visits such as the US and Russia (Horn studied Russian himself, and has also worked as a translator).

One of my favourite essays here that I just want to go back and read right now is titled The Georgian Military Road anddescribes the car journey Horn takes with a Georgian friend (who is hosting him) to a tiny church in the Georgian mountains. This essay blends in history of the place with Horn’s experiences of studying Russian in Russia, living with a Russian host, feeling fascinated by the culture but also coming to terms with the fact that Russia is an extremely homophobic country in which violence against the members of the LGTBQ+ often goes unpunished, which means is not safe for people to live there openly queer.

Here you have an example of a paragraph describing the moment Horn finally gets to Saint Nino’s church:

‘Making the sign of the cross, I turned from Saint Nino, congratulated her on her reappearance, and walked outside onto a ledge that wrapped around the church. I zipped my coat against the cold, watched vultures crest through the mist. Fog slithered across the ground, around the church brickwork, blotted sky and earth, only to clear in a gust of wind and reveal the drop gaping inches from my feet. I shuddered, stepped back. Around me, visitors took selfies, shouted and pointed when the air thinned, cramming into sudden shots – smiles, peace signs, star jumps. Behind me, I could still hear the monks murmuring devotions on the altar step, could taste the frankincense. I turned from the ledge and vegan my descent to where Ivano waited, far below, in the mountain’s mouth.’ (p.85-86)

The writing is so effortlessly beautiful – and so visual – I was there, in that moment, with the author.

Another chapter focuses on Horn’s experience with being assaulted when he was in their twenties – and how this led to a health crisis that left him incapacitated for months, in excruciating pain, unable to write, study, even read. This was a chilling chapter to read, very difficult actually. Horn gets assaulted in England, where I live, and it happens when he’s going to the swimming pool in the very early morning. It was hard to read because I go running in the very early morning too, and also in winter, when it’s dark and there’s barely anyone in the street. One of the most terrifying things is to read the police’s reaction to the assault – almost a ‘well, but what were you doing in this area alone at this time’ almostimplying that being assaulted is his fault, really.

Part of Horn’s recovery journey includes tattooing – writing in his skin sentences from his favourite books that he can’t read anymore – an experience he dwells in through a beautiful essay about the tradition of tattooing and queerness. And, of course, there are also essays on swimming, on the sea, on Horn’s life-long fascination with water and the creatures living in it.

I loved this book so much I pretty much went to buy my own copy as I finished it.

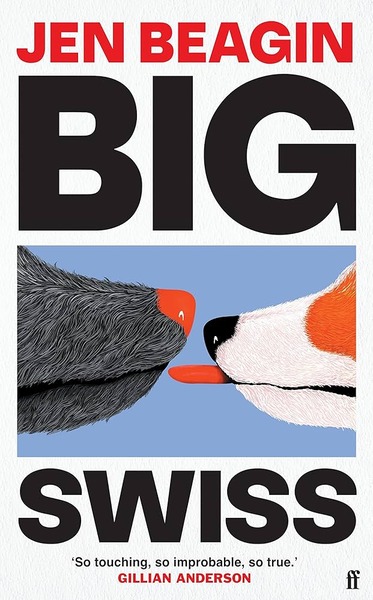

Big Swiss by Ken Beagin

The premise of this book sounded very interesting: a woman who works transcribing the therapy sessions of a psychologist expert in sex in a small community in uptown New York (Hudson) – and falls in love with one of his female patients by listening to their therapy sessions.

The first thing to note here: this is a satirical piece, so all the characters are weird and slightly unhinged, and that, almost immediately, becomes the normal of the novel. For example, the main character, Greta, lives with her dog Piñón in a massive dilapidated house with a kitchen full of bees (yes, there is a hive in there that the house’s owner, Sabine, refuses to get rid of). The psychologist she works for goes by the name of ‘Om’ and often tries kundalini breathing exercises and chants with their clients. Sabine, Greta’s landlady and friend, is rich enough to own a massive house with its share of land in Hudson but not rich enough to fix it and make it actually liveable – she spends her days growing weed that then she sells to the community and stealing things in shops (apparently more for the thrill than anything else) that she hides in her dense mane of hair.

This is also a story about trauma and how people react to it. Greta is forever marked by the early death of her mother, a woman who always suffered from depression and ended up dying by suicide when Greta was only fourteen. As often happens, Greta herself also suffers from depression and often imagines her own death. She falls for Flavia, Om’s client, a woman who has survived a brutal attack (which is described with chilling detail in the therapy sessions) and yet refuses to accept the idea that the attack has anything to do with her inability to orgasm and have a satisfactory sexual relationship with her husband.

Some would say that the character of Flavia is not believable – she is a very rational person (which makes sense, as she’s also a doctor, a gynaecologist, of all things) she is assertive and knows what she wants. She has also decided that what happened to her was horrible, but she easily rationalises it by admitting to her therapist that she put herself in a vulnerable situation (by accompanying a sketchy man she didn’t really know to his house in the middle of the night). Flavia, to me, was the most interesting character. I know people who think in very similar ways and have this ability to easily separate the rational from the emotional and the visceral. Perhaps we are more used to seeing characters like this who are male instead of female, which is why I thought Flavia was especially interesting (even more than Greta). It also reminded me of Virginie Despentes’ reflections in her book King Kong Theory – how violence and assault don’t necessarily and fundamentally destroy women turning them into the vulnerable, broken creatures they have always been (and how the threat of assault and the loss of ‘purity’ has always been used to control women and keep them in their ‘allowed’ spaces).

Some spoilers ahead now as I dwell on what I enjoyed (and didn’t enjoy) about this book.

I thought the first half, which focused on Greta’s obsession with Flavia, was brilliant. Getting to know Flavia only through the transcriptions also worked very well to create a sense of mystery. Now, once Greta and Flavia met each other in person – which the novel had already established as a very likely possibility, as the community in Hudson is small and everyone knows each other – I felt that much of the narrative tension dissipated. I wanted to believe in their relationship so badly. They are both fascinating characters – Flavia is young and cold-headed, Greta is twenty years older but behaves like a teenager. And yet, there was something about their romance (if one can call it that) that never quite clicked for me. This wasn’t as queer as I wanted it to be, and in that sense, it lacked nuance to me. (Instead of two women imperfectly loving each other or lusting for each other they seemed more like two women who had to be together for the sake of the plot but they didn’t quite understand why). The last third of the novel dragged a bit with the different plot strands seemingly going nowhere. The ending included two mini donkeys (of course it did), a lot of unsolved questions, and Greta’s final enlightenment.

(After reading this book I had a conversation with my sister, who is a psychologist, about Alfred Adler, the founder of the individual psychology, who theorised that trauma shouldn’t define us as individuals because all we have is the present moment. I suppose considering Adlerian philosophy could be a good idea to contextualise some of the themes found in this novel…)

Good Material by Dolly Alderton

I’m not doing this on purpose – but it seems that the books I’m picking these days share similar themes. This book, like Leslie Jameson’s Splinters, is the story of a woman who decides to finish a relationship because she’s fallen out of love. Because she discovers she’d rather live on her own than share her life with her male partner (which I find so fascinating because fiction has focused so much on stories about women finding their ideal partners, and supporting them through their lives). What makes this particular novel unusual is that this story is told from the perspective of Andy, the man who gets left behind. And he doesn’t even understand why.

This is my first time reading Alderton’s fiction – I read her collection Dear Dolly earlier this year. I have to say I was pleasantly surprised – Alderton is definitely a good writer, and this was a quick read for me, and very enjoyable, as I got into the characters and the story pretty much from the first page.

Andy is presented with nuance and complexity – some people may find him unlikeable but, to be fair, I empathised with him from the beginning. He is heartbroken – a woman he thought he’d spend all his life with has left him simply because she’s fallen out of love. His career is also in shambles – he’s a stand-up comedian but not a very successful one. His (male) friends don’t seem to have all that much time or emotional bandwidth to support him through the worst time of his life.

Much of this book is sad to read – even though Alderton is excellent at adding comedy here and there, especially the bizarre or cringe kind. It features Andy’s downfall – because he just doesn’t cope well (mostly at all) with Jen, his girlfriend, leaving, and he tries everything he can think of to forget her with little success, including hiring a personal trainer to get fit, getting black-out drunk, dating a younger woman… and yet, the pain is still there.

The cast of characters around Andy is also realistic – his best friend, Avi, married to Jen’s best friend, Jane – his pack of guys, his loving mum (who raised him as a single mother) and his quirky landlord. Andy spends a lot of this book hating Jen and then trying to understand her. One of the most memorable scenes of this book is the conversation Andy has with his married friends, Avi and Jane, in which Jane tells him that actually, many women’s dream is to live on their own. Avi and Andy are shocked to hear this – who wants to spend their life alone? – but Jane insists that many women do.

This is perhaps the most interesting aspect of the novel – Jen’s decision to terminate a relationship because she doesn’t want to play the role of the girlfriend, of the potential mother and wife because she prefers to focus solely on herself (something that men have been doing for centuries and are hardly criticised about).

(Big spoiler here). One of my favourite sections of the book was the coda at the end – when we get to hear directly from Jen’s perspective and discover that she just doesn’t want to be in a romantic partnership.

That said, there were a few things here I felt ended up too neat – and a tad unrealistic, especially considering the grim realism of most of the novel. First of all, Andy’s career finally taking off – great for him, but a bit of a deus ex machina that the break-up is what actually inspires him to write his best act yet? Then Jen quitting her job to go travel the world – sure, that’s my fantasy too, but again, a bit unrealistic? A part of me wishes that this was a book written from both perspectives (Andy’s and Jen’s) in a more balanced way but that’d end the mystery that permeates most of the book – which is why did Jen leave Andy if there was nothing wrong with their relationship in the first place?

A heartbreaking, relatable and funny novel about heartbreak and relationships.

One thought on “A Queer Summer: July 2024 Reading Log”