Small things like these by Claire Keegan

This is a novella, so a quick read, yet it left a big impression on me and I’m still thinking about it. Set in Ireland in 1985 it follows Bill Furlong, a coal merchant in a small town where everyone knows each other. The day before Christmas he goes to the nearby convent to make a delivery and finds something in the coal bunker that shouldn’t be there. Hence, he’s faced with a dangerous moral decision – to speak up against the nuns, who are very powerful members of the community or keep living his life as quietly as he’s used to.

This dilemma is a powerful one – to tell the truth and stand up for others often requires a sacrifice that not many of us are willing to make. Being good and decent can also mean paying a high price. It’s easy to empathise with Bill from the very beginning because he’s a hard-working man with the best intentions. He has an interesting upbringing many would have frowned upon back in that time – his mother had him when she was sixteen years old and while working as a maid for Mrs Wilson the richest woman in town; he doesn’t know who his father is. Against all odds, Mrs Wilson lets mother and baby stay in her household and acts as a sort of kind relative towards them both. As an adult, Bill has a job, a wife, and five daughters. All of these are important details that will foreshadow the protagonist’s final decision.

The writing here was superb, as was the characters’ progression and the tension build-up. There’s a chilling scene with Bill in the convent – because it’s the day before Christmas the nuns invite him in for a tea. This is an excellent example of how to subtly communicate something horrifying through layered dialogue and a handful of well-chosen details. This is scene that I won’t = forget it any time soon. Definitely one of my favourite books from 2023.

The Solace of the Common People by Angela K Smith

An interesting read, written by a colleague, on a genre I’m finding myself really attracted to these days: speculative historical fiction. It follows Richard III, who I actually didn’t know much about (yes, as a diehard republican I rarely find myself in the mood to read stories about queens and kings). When I started reading the book I thought he was just, well, an English king, and pretty early on I realised he was the evil king who killed the princes in the tower (if you are not familiar with the story, you can read about it here.)

This book combines two different timelines, a future one in 2125 and a past one (with Richard III) in 1485. It takes a while to see how they are connected but the twist does come, and it’s a good one. While reading Richard III’s timeline I found myself thinking of books like Game of Thrones, because there’s a lot of betrayal and nuanced politics in there. What I found most fascinating about this book is how it shows the intricacies of power – how some of the most influential people are those who remain in the shadows, nimbly manipulating things. But, most importantly, this is a book that depicts main characters who never really wanted to hold power but find themselves in a position where they are forced to. And I think, paradoxically, these people – the ones who actually don’t want it – are the best to be placed in authoritative roles. In Plato’s words, ‘only those who do not seek power are qualified to hold it.’

The Sanatorium by Sarah Pearse

Another crime fiction book I read because I want to understand this genre a bit more. So far it’s been a bit hit-and-miss for me. I enjoyed Nine Perfect Strangers , but wasn’t as fond of The Doll. This one falls somehow in between. It had a promising premise: it’s set in a Swiss hotel in the middle of the mountains that becomes isolated after a snowstorm. What can go wrong here, right?

The main character is your classic tortured detective with a dark past, Elin, who’s come to the Swiss hotel with her partner to her brother’s engagement party.

The descriptions of place – the Swiss mountains, the snowy landscape, and the sanatorium reconverted into a modern hotel – were one of the things I enjoyed the most about this book. It’s not a secret that I’m obsessed with mountains and I’m also fascinated by places with a dark history, such as the TB sanatorium of this novel. There are a few hints here and there of the building’s murky past and, in that sense, the book ends up delivering. I found all the research Pearse has done around Swiss sanatoriums very realistic and well-used in the plot.

Elin’s complicated relationship with her brother Isaac was something I also thought was well integrated into the story. I always want to see more sibling relationships and their nuances portrayed in fiction (instead of the stereotypical heterosexual couple being the focus) and I found it realistic and engaging. It added mystery to the plot as both of them shared the same complicated past.

What didn’t do it for me was the final revelation: I struggled to believe what I was told by different characters as well as their reactions to specific events. Sarah Pearse has done some very good research into the stories of sanatoriums – being places not only to cure TB but where families put people (especially women) who were considered ‘morally ill’ to get rid of them. I wanted more of this in the story, and personally, I think this was where the real horror lay.

Memorias de Abajo (Notes from Down Below) by Leonora Carrington

I’ve been fascinated with Leonora Carrington’s art since the first time I saw her paintings in an exhibition at the Thyssen Museum in Madrid. I’m just infuriated that we didn’t study her (or her contemporary, the also extraordinary Remedios Varo) in Art History in my secondary school and that she’s not all that well known in Europe.

This past April I was in Madrid and I heard that there was an exhibition completely focused on her work and of course, I was there as soon as I was able to. It didn’t disappoint and I still think about some of her paintings, which are a very distinctive mixture of surrealism, dreams and myth. In the exhibition they had a documentary by Kim Evans in which she had been interviewed in Mexico in 1992 – when she was in her seventies – and I was in awe so to see how intelligent and charismatic she was on camera.

Memorias de Abajo (The House of Fear: Notes from Down Below in its Englisg translation) is a short book that features what Carrington wrote about her traumatic experiences during the Second World War while she was in Europe, which culminated with her being sent against her will in a sanatorium in Santander, in the north of Spain.

Leonora Carrington was in her early twenties when the war started. She was living in a small French village with her lover, Max Ernst, in a dilapidated house she’d bought and then fixed and decorated with original paintings and murals. Because Ernst was a Jew he was taken away by the military and Leonora was left alone without any support. She was already estranged from her aristocratic English family by then, so couldn’t go to them. A couple of friends convinced her to leave the house and drive with them to Spain, as this country was, technically, not participating in the war. From the very beginning, Leonora was very distressed and suffered from acute anxiety and panic (but who wouldn’t, in the midst of a war). The moment she crossed the frontier and got into Spain she was already enticed by the strangeness of the landscape. She made it as far as Madrid before she realised she was trapped there with almost no friends and no money, dependent on her father to get the papers she needed to travel further, and she feared she might not see Ernst ever again. Before I read this I didn’t know that Leonora Carrington had such a traumatic stay in Madrid – where she was also sexually assaulted by a group of Spanish soldiers – and so I felt weirdly ashamed of my hometown for a moment there. After all this, she had a proper mental breakdown and her father arranged things so she was sent to a sanatorium in Santander, a city in the north of Spain.

Leonora’s stay in the sanatorium was terrifying, and one of the hardest bits to read. The sanatorium’s (all male) doctors had very questionable treatments. She was humiliated, punished and gaslighted on a daily basis. In the midst of coping with her own trauma, she had to learn to fight them and survive, which more often than not meant conforming to whatever version of ‘sane’ they believe in.

The story finishes with one of the most amazing events in Leonora Carrington’s life. After convincing the sadic Dr Morales that she was finally cured, she left Santander with her Irish maid and, following her father’s orders, went to Portugal to take a boat to South Africa, to another sanatorium where her family planned to make her stay (who knows if for her whole life). When they were in Portugal, Leonora managed to escape by getting into a restaurant’s toilet and leaving through the window. She went on to her friend Renato Ledux, who was the Mexican ambassador, and who agreed to marry her so they could both escape the country and travel to the States.

This is a difficult read. Leonora Carrington wrote this in 1943, in French, when she was with a different psychiatrist in Mexico, trying to make sense of her trauma once and for all. It’s an exorcism for the artist, as well as an exploration of the world of her own dreams and subconscious mind. A very eloquent account of losing one’s mind (and finding a way out, somehow). Moving and chilling and a critique of the horrible way some people with mental struggles were treated in the twentieth century.

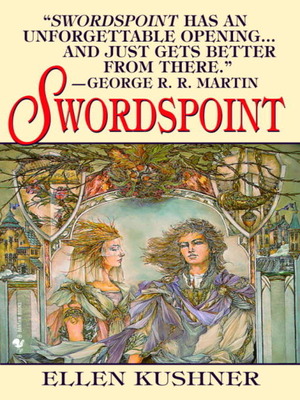

Swordspoint by Ellen Kushner

This was a re-read – which I rarely do (there’s not enough time to read all the books I want to read in my lifetime, I’m sure!) But this book made a big impact on me when I first read it. I was only 18 years old and I hadn’t found many books that featured queer characters yet. I was thirsty for them and when a friend recommended this one I read it (and I did so in Spanish, because back then I wasn’t reading all that much in English yet). So, more than years later, I wanted to know what the book was in its original version and if I still liked it.

The writing in this book is superb: Ellen Kushner has an excellent eye for detail, world-building and character description. She can also be incredibly funny, and the way she describes the aristocrats in this book – as a bunch of silly/machiavellian degenerates – made me laugh out loud. The novel is set in a fantasy world in a place called Riverside – home to delinquents, underdogs and rebels, the kind of place that the nobles from the Hill don’t dare to even put a foot on. The world-building is nuanced and layered and through the novel you inhabit these spaces and get to meet their picturesque inhabitants.

Another thing I love about this book and I found refreshing is how queerness is not really questioned at any point – some characters are queer, some characters aren’t and that’s it. Richard and Alec, the protagonists, have many problems, but the fact that they are together is not one of them. Plus Alec is such a despicable, tender, annoying and charismatic character. You can tell Kushner adores him and he gets some of the best lines in the book:

The smell of frying fish made the swordsman’s stomach lurch. It was his young gentleman, the University student, wrapped in his scholar robe, hovering like a black bat over the frying pan in the ornamented fireplace.

“Good morning,” St Vier said. “You’re up early.”

“I’m always up early Richard.” The student didn’t turn around. “You are the one who stays up all night killing people.”

(p.5)

The plot in this book unfolds nicely with some unexpected twists and turns towards the end. I have read that Kushner was criticised by some for not having many significant female characters in this book, which is something she consciously tried to remedy in the next novels she wrote set in this same universe. I can see that in this novel specifically we mostly have male characters. But we also have a really deliciously twisted female villain who I thoroughly enjoyed reading. And I don’t think a book can do everything, everywhere at once. I think in terms of tone and how it addressed some fantasy tropes (around class, for example) this book is really doing many interesting things. Definitely recommend it if you like fantasy, comedy of manners or just a well-crafted read.

Anarquía Relacional (Relationship Anarchy) by Beatriz Herzog, Roma de las Eras, Belo C. Atance and Nazareth Dos Santos

I picked this graphic novel while I was in Madrid because I thought both the cover and the topic looked really interesting, and I really love when graphic novels mix critical theory with philosophy and fiction and all sorts of other fields (that’s why I love Alison Bechdel’s Are You My Mother? which I think is absolutely superb).

This was one of the most fascinating books I’ve read this year because it introduced me to the concept of relationship anarchy which I was not really familiar with. But it had the word ‘anarchy’ in it, and, as someone who’s always felt aligned with the term I was really curious about it.

Relationship anarchy may be a new-ish term – which apparently comes from this blog entry – but it deeply aligned with lots of things I’ve always felt true at an essential level. Mainly, the hierarchy of relationships (meaning: that the relationship with a potential partner is the most important one, followed by close family, leaving friends in the periphery) is utter and complete nonsense. It may be because I grew up in quite a small family unit or because friendship is an essential part of my relationship web as someone who is an immigrant in a country where they don’t have any biological family but I find this ‘decentralisation’ of romantic love very freeing and inspiring. I think the book also managed to communicate lots of interesting ideas from anthropology, sociology and gender studies in quite a nuanced way, with the fictional parts illustrating what this relationship anarchy may look like in practice. I really, really liked that romantic love wasn’t the focus (so, relationship anarchy is much more than, say, polyamory). Plus the bibliography from this book has given me lots of sources on this subject I really want to read now – in fact, I just bought Crítica del Pensamiento Amoroso (Challenging romantic thought) by Mari Luz Esteban, a scholar from the Basque Country, and I’m finding it really enlightening. To sum up, if you are intrigued about the concept of relationship anarchy or know someone who may be, this is a great read to get a quick but solid introduction.

3 thoughts on “Enlightment: April 2023 Reading Log”